November 18, 2025

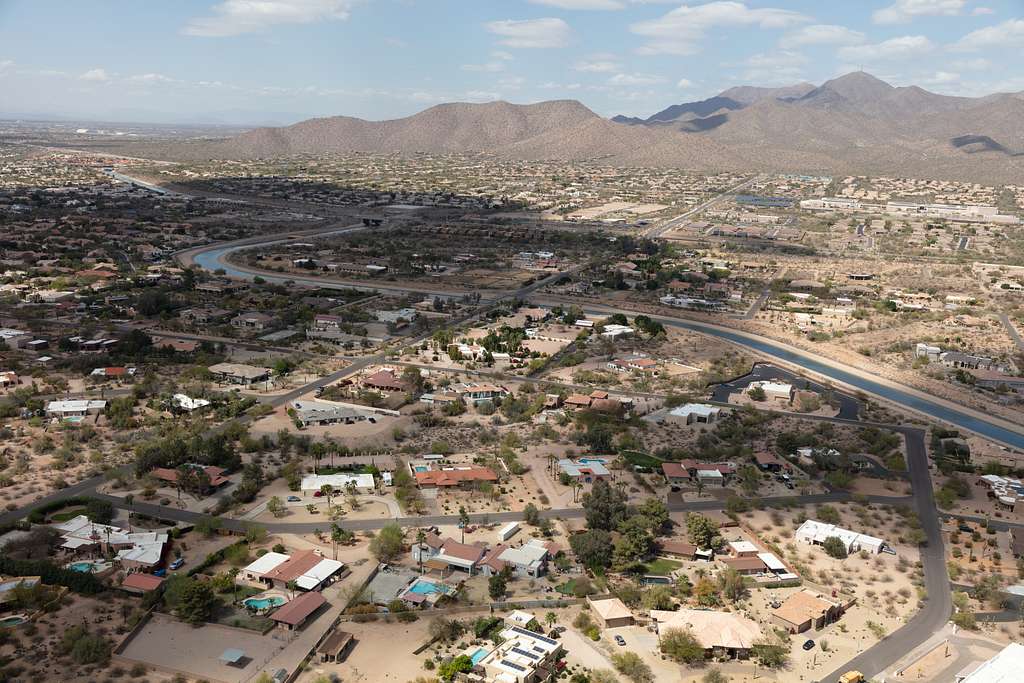

Transportation systems, norms, and rules can vary widely across international borders. Take traffic laws, for example—in the U.S., turning right on red is a common practice, while in most other countries it’s prohibited unless explicitly allowed. In the U.S. and most European countries, a driver will climb into the left-hand side of a car, whereas in countries including the UK, Australia, Japan, and India, drivers will sit on the right. Cities’ urban forms vary based on the time periods in which they were built and expanded; for example, European cities often have narrow, more walkable streets, while North American cities tend to prioritize wide arterials and car access. Population density also plays a major role: the density of Manila, the Philippines, is 111,002 people per square mile while Phoenix, Arizona is 3,232 people per square mile, leading to very different cost-benefit scenarios when considering transportation routes.

Manila, the Philippines is one of the most densely populated cities in the world. Photo by Patrick Roque on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Contrast that with the spread of Phoenix, Arizona. Photograph in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Cultural attitudes further influence how systems function. In Australia, roadside breath tests are routine and widely accepted as a public safety measure, whereas in the U.S., they’re more likely to be viewed as intrusive or reserved for extreme situations. And while private vehicles dominate in many American cities, public transit is the primary mode of travel in places like Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong. You might even find different types of vehicles depending on where you are in the world, such as keke napeps (bright yellow motorized tricycles) in Nigeria, jeepneys (military jeeps converted to minibuses) in the Philippines, and chivas (colorful, open-sided buses) in Ecuador.

A colorful, open-sided bus known as a chiva in Ecuador. Photo by Jorge Láscar on Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

Keke napeps offer quick, low-cost rides in Nigerian cities.

These differences underscore a key point: success in one place does not guarantee success in another. A transportation idea can’t be copy+pasted without close consideration of the context and cultural norms. However, overemphasizing these differences draws our attention away from how much is fundamentally the same in metropolitan areas everywhere. We assume that what works in one place could never work in another, but are major cities across the globe actually more different than they are alike?

Every City Needs to Move

Major cities around the world share a remarkably consistent transportation foundation. Streets and road networks form the physical backbone of urban mobility, supporting a mix of modes—walking, cycling, public transit, private vehicles, and freight. Most cities experience peak-hour congestion, rely on regulated intersections with traffic signals, and maintain central hubs where people transfer between public transportation systems. And of course, people walk in every city, even if the quality of the pedestrian infrastructure varies.

The consistencies aren’t surprising, because cities everywhere are built around a common set of needs: people must move between homes, jobs, and resources. Recognizing the commonalities among every city’s structure, goals, and challenges opens the door for learning from one another.

In this article, we’re exploring how the international experiences of current and former Kittelson team members have informed transportation improvements both in the U.S. and abroad. To learn how transportation ideas travel internationally, we interviewed five industry professionals with significant work experience outside their home country: Carla Kleynhans, who works for a consulting firm in Cape Town, South Africa; Peter Bilton, who runs a consulting firm in Brisbane, Australia; and Kittelson’s David Laurens, Nick Meltzer, and Paul Ryus, each of whom brings a unique international lens to their projects. Through these conversations, we’ve compiled examples of ideas that have successfully voyaged—and evolved—across contexts, showing how openness to learning from others can unlock creative solutions.

A Global Exchange of Ideas

Carla Kleynhans is an engineer with Innovative Transport Solutions (ITS) in South Africa. In 2021, Carla spent nine months working in Kittelson’s Portland, Oregon, office on an international exchange. She says what surprised her most about the experience was not any wildly different norm, guideline, or idea, but how similar the working environments were.

“I wasn’t expecting how easy it would be to adapt in terms of work-related things,” said Carla. “We all use the Highway Capacity Manual, so I didn’t have to learn all new standards. Of course, I had to learn Oregon’s specific requirements, but that’s the case in any new city.”

David Laurens, a planner in Kittelson’s Orange office, similarly shared that the skills he developed in the 10+ years he worked in his home country of Colombia have translated well to the projects he’s contributed to since moving to the U.S. For example, working at times with limited data in Colombia taught him to be strategic and efficient with the way he used that data. In the U.S., he’s applied that experience helping transportation agencies develop high-level analysis tools that purposefully aren’t resource intensive.

“Many ideas can be adapted from one context to another,” said David. “If you look through Colombia’s design manuals, you’ll notice a lot of these documents draw from U.S. and European guidelines.”

Likewise, David acknowledges that the U.S. could glean valuable transit planning lessons from Colombia, whose bus rapid transit (BRT) systems have become global inspirations for robust and successful public transportation. Through BRT, Bogotá is tackling congestion by finding ways to move people rather than cars, and the results have been impressive reductions in crashes and greenhouse gas emissions.

Colombia’s bus rapid transit systems have become global inspirations for robust and successful public transportation.

“In the U.S., we have issues with people accessing transport because we rely on private vehicles. It forces people to put a lot of their resources into buying cars,” said David. “The way the Colombian central government has worked through the technological, legal, and financial components of restructuring transit systems, in mid-size as well as larger cities, offers lessons to other countries dealing with congestion and safety issues. Initially, it was figuring out how to provide transportation to urban areas where density was driven by poverty and unplanned development. In the 2000s, the focus shifted to more proactive planning, combining government resources with private investments to develop a world-class bus rapid transit system that moves more people than many metro systems around the world, at a much lower cost.” Other countries can learn from the Colombian system’s efficiency and how it considers the needs of underserved neighborhoods. For example, the system uses flat fares so that longer commutes (which tend to correspond to lower income areas further from the city center) don’t lead to higher transportation costs, and feeder buses that connect residential areas to the main corridors are included in the flat fee to use the system.

The International Journey of the Roundabout

For another example, let’s track an idea that, despite initial hesitancy, has gained traction in the U.S. following success in other countries. Modern roundabouts are becoming a familiar part of the U.S. transportation landscape, but their path to acceptance in the States has been lined with resistance. As Peter Bilton, who resides in Brisbane, Australia, noted, the U.S. had a very different starting point compared to the UK, Australia, and Singapore, where roundabouts have long been standard practice.

“In Australia, installing a roundabout is not controversial; in fact it’s often thought of as the expected solution in many new land developments,” he said. “Comparatively, roundabouts are a fraction of the U.S. network.”

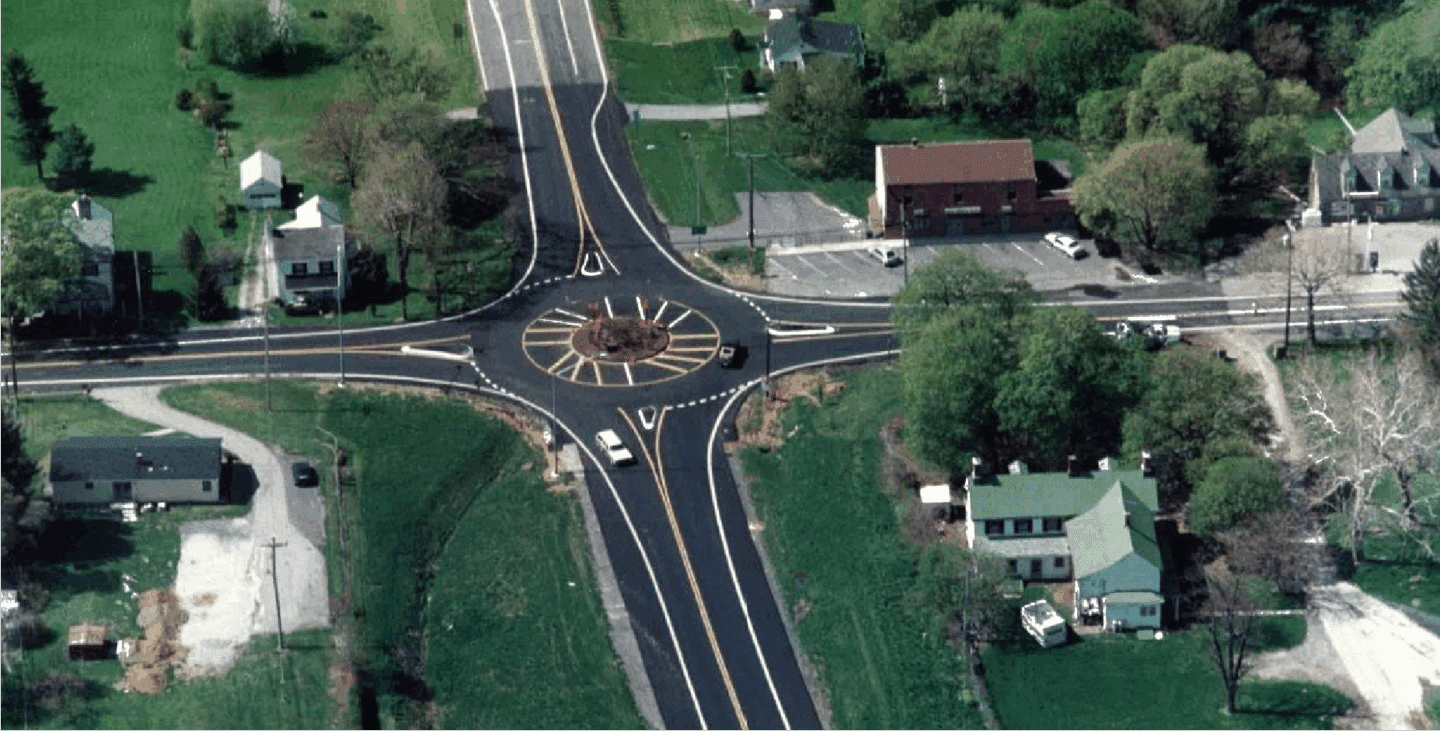

In the U.S., older-style traffic circles had fallen out of favor by the 1950s due to crash rates and congestion. But in the early 1990s, engineers in Maryland began digging into the research as they explored alternatives for a problematic interchange on the I-495 Capital Beltway. They were struck by international case studies showing roundabouts’ potential to reduce severe crashes, bottlenecks, fuel consumption, air pollution, and construction costs, and they reasoned there had to be major differences between modern roundabouts and traffic circles. After learning more from other countries and defining the features that differentiated modern roundabouts from rotaries, they proposed a modern roundabout as a solution for the interchange—a concept that faced strong public opposition, especially in the small town of Lisbon, Maryland, where residents were skeptical of the unfamiliar design.

To start small, the Maryland State Highway Administration (SHA) installed a temporary roundabout and worked closely with a citizen task force. After three months, the task force requested the temporary roundabout be made permanent as soon as possible. The State began constructing more roundabouts, developing design guidelines based on Australian manuals, and producing educational materials. As results began to show, interest from other states grew. Maryland’s program became a model, and transportation professionals from across the U.S. and Canada visited to learn from its success.

The temporary roundabout in 1992. Photo from Maryland State Highway Administration.

The constructed roundabout in Lisbon, MD - the first modern roundabout in the state. Photo from Maryland State Highway Administration.

Today, the Roundabouts Database tells us there are more than 10,000 roundabouts in the U.S. and Canada, and the number continues to rise. While some places still face skepticism or opposition to converting signalized intersections to roundabouts, FHWA has recognized roundabouts as a Proven Safety Countermeasure, and public familiarity and acceptance has come a long way.

A Global Perspective on Day-to-Day Projects

Global influence can also play out in smaller, more immediate ways. Lessons from other countries don’t always call for new intersection types; sometimes, they show up in the details of a bus lane or the layout of a tunnel.

Carla says Portland’s pedestrian-focused approach has influenced how she thinks about urban design. She brought many ideas back to Cape Town after her exchange, including a creative solution in which the lane of a new bus line permitted bicyclists to share the space. That design detail has helped inform similar projects in her home city.

Nick Meltzer, who works in Kittelson’s Eugene, Oregon, office but regularly teaches study abroad courses in Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands, says his work on a tricky intersection retrofit was shaped by his time biking in these countries. With limited ability to fully redesign the intersection, he used a light-touch, quick-build approach, adding pavement markings inspired by his international experiences to guide cyclists clearly and safely through the space. He’s also working on a shared-use path project that may include an undercrossing beneath a railroad and is looking to Dutch tunnel design principles, which emphasize the safety and comfort of people using the tunnels at night. Their strategies include angling walls to make the space feel less constricted, placing skylights to keep the tunnel well-lit, and keeping brush several feet away from the path for improved visibility coming in and out of the tunnel.

Dutch tunnel design principles emphasize the safety and comfort of people using the tunnels at night. Photo by Fantaglobe11 on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The lessons apply to organizational operations, too. For example, Peter says his time at Kittelson influenced how he collaborates and leads back in Brisbane. He appreciated the culture of cross-disciplinary learning and how all team members at Kittelson have the opportunity to raise their hands for projects they’re interested in, and he’s worked to embed that mindset into his own firm, Point8.

Peter Bilton (right) enjoys an American football game with Kittelson colleagues during his U.S. work exchange.

Today, Peter runs an Australian transportation consulting firm called Point8.

These examples show that while global experience can shape big-picture thinking, it can also influence the small decisions that make up transportation projects and the organizations that carry them out.

When Does an Idea Translate?

Okay, so how do you know when a solution born in Bogotá has the potential to succeed in Boston? When can an idea be used, when should it be adapted, and when is it simply not practical? Three principles emerged from our conversations:

1. Explore with an open mind and be willing to challenge your assumptions.

When you hear about the Netherlands’ latest bike intersection treatment or Denmark’s cycle superhighways, how do you categorize the ideas in your mind? Do they only succeed in those countries because the Dutch and Danish have bike fanaticism in their veins? In the study abroad course he teaches, Nick says he enjoys introducing his students to transportation infrastructure in Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands firsthand because learning how it came about grounds the ideas in practicality.

“Many people assume Copenhagen and Amsterdam have always been obsessed with biking, but if you look at history you’ll see critical issues that drove the public desire to transition to safer streets,” says Nick.  “In Amsterdam, there was a movement in the 1970s called ‘Stop de Kindermoord,’ which translates to ‘Stop Killing Children,’ in response to the number of children being hit by cars. A focus on safety is what led to the development of the bike infrastructure we now associate with the Netherlands. In Copenhagen, the switch to building more bike infrastructure was driven by an oil crisis. In both cities, the changes were progressively more successful until now they’re known as biking capitals of the world.”

“In Amsterdam, there was a movement in the 1970s called ‘Stop de Kindermoord,’ which translates to ‘Stop Killing Children,’ in response to the number of children being hit by cars. A focus on safety is what led to the development of the bike infrastructure we now associate with the Netherlands. In Copenhagen, the switch to building more bike infrastructure was driven by an oil crisis. In both cities, the changes were progressively more successful until now they’re known as biking capitals of the world.”

Similarly, we can look at Copenhagen’s cycle superhighways—an innovation often romanticized as a reflection of the city’s deep love for bicycles. But the reality is more practical than poetic. These routes are direct, high-quality bicycle facilities from suburbs into Copenhagen where bicyclists don’t have to stop very often, because major streets might be crossed using under- or overpasses or traffic signals might be timed to give cyclists a continuous “green wave” at average biking speeds. These facilities weren’t built because Copenhageners can’t get enough of their two-wheeled vehicles. Instead, they were designed to solve a specific problem: how to keep people warm while biking longer distances to work and education even in cold, rainy, and snowy weather.

Copenhagen’s cycle superhighways were designed to solve a specific problem: how to keep people warm while biking longer distances in cold, rainy, and snowy weather. Photo: “Snowstorm Crowd 02 - Winter Cycling in Copenhagen” by Mikael Colville-Andersen on Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

Of course, the same conditions don’t exist in every city, so the point here isn’t about turning any innovation into a one-size-fits-all solution—it’s about understanding what need an innovation is addressing, why it works, and whether any of those lessons could translate to a new context.

2. Identify the barriers (beyond “It won’t work.”).

Where does resistance to a new idea come from? As noted, hesitancy to try a transportation innovation born in another place often stems from unfamiliarity or the vague assumption that “it would just never work here.” The key is to understand and articulate what the barriers are:

- Is it a different way of doing things that simply calls for education and awareness?

- Is it a major mode, policy, or priority shift that requires deeper structural adaptation?

- Does a different context render the idea truly impractical?

Take daylighting, for example—a safety measure that prohibits parking near crosswalks to improve visibility. Common in European cities, it’s already supported by existing U.S. engineering standards and curbside regulations.

“Cities already have the ability to control curbside activity, drivers already know how to recognize where parking is prohibited, and engineering standards exist for marking and signing no-parking zones,” says Paul Ryus, who has telecommuted to Kittelson’s Reston office from Denmark since 2009 and whose unique working situation often leads to him being called on for international perspectives on projects. “The challenge in implementing daylighting, then, is the same challenge associated with any change to curb usage (e.g., loss of parking) rather than being specific to the daylighting concept.”

In contrast, Paul notes that edge lane roads (or “advisory bike lanes”) present more complex challenges. These shared-space designs require drivers to yield to bicyclists and pedestrians while navigating a single central lane. Implementing them in the U.S., where awareness of such a concept is low, demands road user education, possible updates to vehicle codes, and new signing and marking standards—barriers that can be overcome, but the time and effort required to gain acceptance of edge lane roads will be greater, requiring a clear vision, motivation, and plan.

Edge lane roads require drivers to yield to bicyclists and pedestrians while navigating a single central lane. Photo from edgelaneroads.com.

Sometimes the barriers are practical reasons a solution won’t translate well. For example, David pointed out that Bogotá’s efficient bus system thrives because of the dense urban environment. In contrast, building a new bus line in sprawling Los Angeles, where he now resides, would require more infrastructure to serve fewer people. Los Angeles can draw valuable lessons from Bogotá’s planning process, but the differences in geography and density of the two cities means the solutions will probably look different, too.

In all of these scenarios, identifying and categorizing the barriers opens the door for a pragmatic discussion about what the true lessons are and how ideas could be reimagined to meet similar needs in a different context.

“We need to acknowledge and name the differences up front,” says Nick. “I then find I can usually give examples of how cities are not so different after all. I encourage the belief that cities are cities: people live and work and socialize in all of them, and they are more similar than different. No, you can’t just drop an idea into a different context, but you can still learn from it.”

3. Be mode agnostic.

It’s tempting to label countries by popular transportation modes—whether cars in the U.S., buses in Colombia, or bikes in the Netherlands. But these identities can obscure the real question: What’s the best way to move people through a particular place? Effective transportation planning isn’t about loyalty to a mode; it’s about matching solutions to needs.

Paul reflects on this dynamic based on his experience living in Denmark for the last 15 years: “The larger cities here underscore the importance of land use and transportation working together. When I lived in Copenhagen, the only times we needed to drive were to visit people outside the region or to shop at IKEA,” he said. However, in the smaller city where he now lives (about 25 miles from a larger urban center), people drive more often. “Local destinations are still within walking or biking distance, but many people work elsewhere. Train and intercity bus connections are less frequent and often don’t take you all the way to where you need to go. People own cars to get to work and then use them for other daily activities.” While Copenhagen boasts high rates of bicycle usage, smaller Danish cities are seeing those rates decline.

This contrast highlights a key point: mode choice is shaped by land use, connectivity, cost and convenience—not national identity. To plan effectively, we must untangle cultural assumptions and focus on what works best for each community’s geography, economy, and daily rhythms.

Go See for Yourself!

As with most ideas, new transportation concepts are best understood by experiencing them firsthand. If an idea feels unfamiliar or difficult to visualize, sometimes the most effective step is to go see it in action. You’ll likely return with more inspiration than you bargained for!

“Don’t be afraid to pursue an opportunity to work or study abroad. It will only enhance your career and life experience,” says Peter. “You’ll learn to challenge your own assumptions and boundaries and resilience to adapt and work in an environment that’s less familiar.”

Nick has seen this transformation happen through study tours he’s led, where transportation professionals from Oregon spend two weeks abroad learning alongside students.

“Study tours are a good way to make ideas translatable. We challenge our students to think, why can’t this be done back at home?” he says. “Having the shared experience and learning makes the ideas come alive.”

Even if you don’t have an international flight scheduled in your airline app, you can still be intentional in broadening your perspective when looking for examples, staying abreast of research, and following industry updates. Many cities and agencies share their work online through videos, case studies, and publicly available design guides.

By keeping an open mind and a curious eye, we can learn from one another and adapt ideas across borders in ways that make sense locally. Not every solution will translate perfectly (and that’s okay!)—what we encourage is approaching new ideas with a willingness to understand, test, and tailor them.

In addition to the credited authors above, we thank Carla Kleynhans and Peter Bilton for their important contributions to this article.