May 20, 2020

Baltimore’s dockless vehicle program offers a wealth of insight for cities assessing the viability of e-scooters in their transportation system, particularly during COVID-19.

Baltimore’s dockless vehicle program – which was officially launched in 2019 following a one-year pilot – has several noteworthy components, including a hands-on approach to vendor management and close collaboration with the Baltimore community.

But perhaps the most defining piece of the program is the rigorous equity requirements.

20 zones around the city are designated as “Equity Zones.” Equity Zones promote dockless vehicle access in neighborhoods underserved by Baltimore City transportation systems. Most Equity Zones are sited in historically underserved neighborhoods, which have been subject to housing and transportation discrimination that has resulted in limited access to private vehicles and reliance on first/last mile connections to transit.

Every morning, each dockless vehicle company that operates in Baltimore City is required to place three vehicles in each Zone, which typically encompasses two to three city blocks. These Equity Zones are much smaller than those in most cities with dockless vehicle programs; the intent is to create locations in which those using text-to-unlock plans can reliably find scooters without the assistance of GPS. Providers are required to have discounts for low-income users, text-to-unlock plans, and cash payment options.

We spoke with Meg Young, Shared Mobility Coordinator at Baltimore City DOT, to learn how these Equity Zones came about, what the outcomes have been so far, and what e-scooter ridership has been like during COVID-19.

Baltimore City DOT applied lessons learned from their bikeshare program as they set up requirements for e-scooter operators.

A contractor gathers scooters for charging in Baltimore's Inner Harbor.

Applying Geography Learnings From a Troubled Bikeshare Program

In 2016, Baltimore City launched a bikeshare program… and it was gone two years later.

“Equity is on everyone’s brain in Baltimore. It’s a buzzword everywhere, but with Baltimore’s unique history, a lot of gaps are more prominent here than in other cities,” explains Meg. “The wealth divide, the division how different parts of the city are served, is not only so present here, but people are uniquely aware of it here. And this is why our bikeshare program never lived up to its potential. There were a lot of issues, but one of the most apparent issues is that it never expanded outside of downtown. It was seen as another appeal to tourists and a mobility option for people who work downtown. Our community didn’t think of it as theirs.”

The day the announcement was made to close the bikeshare program was the same day Baltimore’s dockless mobility pilot program was introduced. The pilot program was assembled quickly in response to the arrival of Bird scooters in Baltimore, but the City already knew that geographic spread would be important. Baltimore became one of the first cities to put in a geographic deployment requirement to ensure scooters would be placed all across the city, not just downtown. Using household income as a metric, they designated some neighborhoods as “Equity Zones” and required that 25% of each company’s scooter fleet be placed in those zones.

New to her role of Shared Mobility Coordinator at the time, Meg’s first priority was evaluating the pilot program. She wasn’t personally sold on e-scooters, and was prepared to make whatever decision the evaluation called for. However, the early data was encouraging.

“We would take snapshots throughout the day to understand where scooters were parked. We saw about 22% of the fleet was in Equity Zones in the morning, then 17% during the day, but then 28% of the fleet would end up there by the end of the day. Those early numbers told us: people are using scooters to commute. This mode does appeal to people with lower income or who have limited access to other transportation options.”

Meg’s team also observed that many of the vehicles were being deployed by companies on the borders of the Equity Zones, often at the edge of whiter and more affluent neighborhoods, indicating that some refinement to the Zones was needed for the impact to reach the intended population.

Early data from Baltimore's dockless vehicle program indicated that e-scooters appealed to people with lower income or limited access to other transportation options.

Refining the Equity Zones

Geographic requirements were reshaped for the formal permit program after many conversations with stakeholders, including bi-weekly meetings with Baltimore’s Dockless Vehicle Committee that were open to scooter companies and the public.

The first requirement was that scooters had to serve the entire city. Scooter companies were required to deploy 5-25% of their fleet in each of nine service areas, cumulatively covering a basic spread over the city.

The second layer to the geographic requirements was a refined definition of Equity Zones. After hearing from community planners, the Dockless Vehicle Committee put together a list of 60 possible zones which were not served during the pilot and pared it down to 20.

“In addition to looking at household income, each of these zones needed to have a connection to something that would give it a reason for ridership, such as connection to transit or proximity to city amenities. Then to make sure we had picked the right locations, we got on bicycles ourselves and biked through those areas to see there were safe places to ride,” says Meg.

“Another thing we had to consider was how to regulate scooters being put in 20 different Equity Zones. We heard from operators that 5-25% of the fleet in each service area was a big enough range, they could figure it out. But putting something like 1% of the fleet in each Equity Zone was too much math. So we made it simple: put 3 vehicles in each Equity Zone every morning. We came up with this in collaboration with operators and they felt it was doable.”

The formal permit program has been in place for close to a year, and Meg noted that looking at ridership data so far, the proliferation of rides taken outside downtown is clearly noticeable. Equity Zones have created pockets of growth.

“We’re still figuring this out,” says Meg. “Not all of the Equity Zones have gone how I hoped, but some have far exceeded expectations. We’re currently taking an Equity Zone deep dive to look at utilization rate, miles ridden within half a mile, and common routes. That’s showing 1/3 of the zones could be ‘graduated’ from being an Equity Zone, meaning companies would likely still deploy scooters there even if they weren’t required. The bottom 1/3 we are thinking of reallocating because there hasn’t been a growth in ridership.

“Overall, though, I can say that Equity Zones have been our biggest area of growth – and that’s especially true during COVID-19.”

E-Scooter Usage in Baltimore During COVID-19

Kittelson’s Ethan Hasiuk, who has been working in-house at the City of Baltimore DOT, has spent the last seven months collaborating with Meg to analyze travel patterns.

“March 14 was the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Baltimore, which was followed by a large drop in e-scooter rides that remained low through the rest of March and April,” says Ethan. “Overall trips are down or remain at zero in 92% of census blocks, as measured by the number of daily origins and destinations combined.”

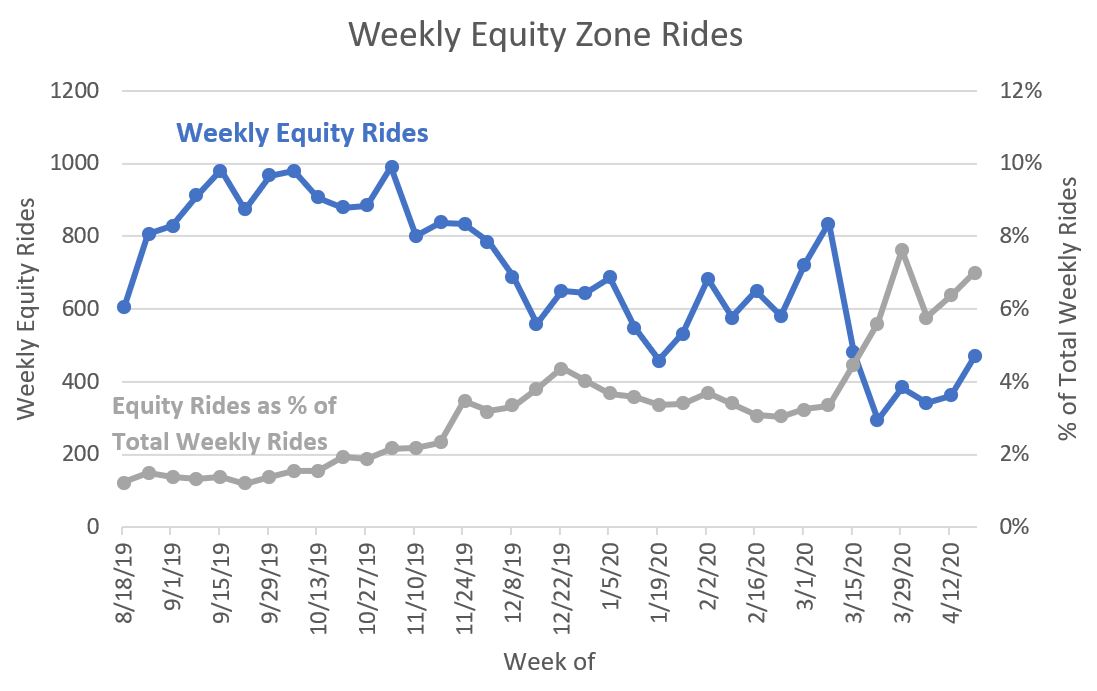

The number of trips that begin in Equity Zones and the percentage of total trips that are Equity Zone trips.

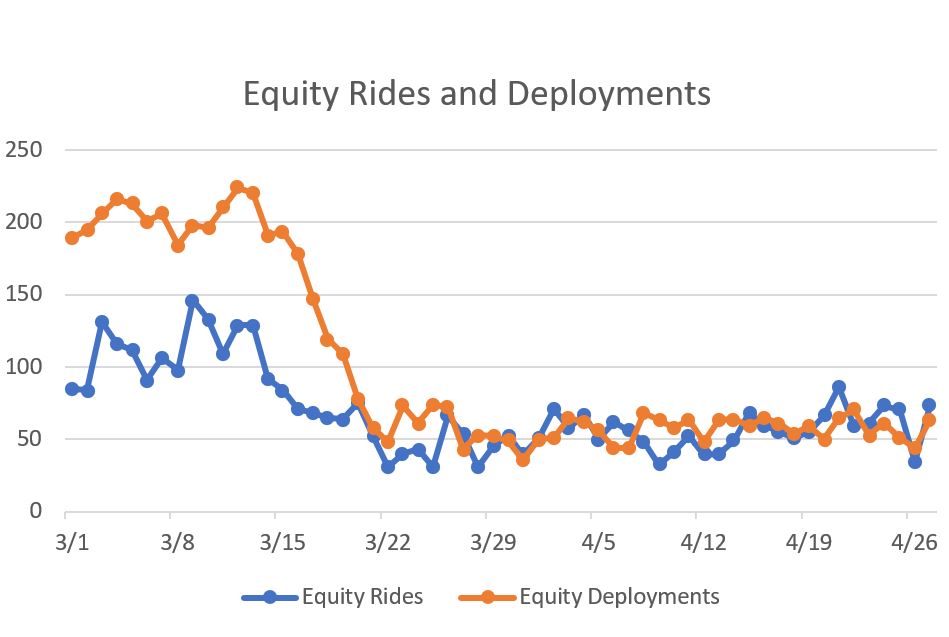

Daily changes in rides originating from Equity Zones, alongside the total number of vehicles that providers have deployed to Equity Zones each day since March 1.

The graph on the left shows the number of trips that begin in Equity Zones and the percentage of total trips that are Equity Zone trips.

“The proportion of Equity Zone rides has increased a bit from the start of the permit, likely due to our tracking and enforcement efforts, but during COVID-19 you can really see it make a jump,” says Ethan. “Simply put, rides originating from Equity Zones have declined less than overall rides.”

This graph on the right shows daily changes in rides originating from Equity Zones alongside the total number of vehicles that providers have deployed to Equity Zones each day since March 1. “Providers have overestimated the decrease in demand from Equity Zones,” Ethan explains. “The data is showing that Equity Zones are where you want to be putting your scooters right now.”

This map shows the change in distribution of trips, comparing pre-COVID-19 ridership (August through February) with data from March and April.

Zones marked by red on the map – colleges, universities, and the Inner Harbor, which is a heavy tourist area – show the biggest decreases in the distribution of trips.

The areas with the biggest increases in the distribution of trips are grocery stores, parks, and some hospitals. Trips to and from Metro stations, even those outside of Baltimore’s urban street grid, are seeing increases compared to previous ridership data.

“During COVID-19, we’ve seen a shift in trips – the percentage of downtown trips has gone down a lot,” says Meg. “We’re seeing rides dispersed throughout communities, with the main destinations being food distribution sites, hospitals, parks. What does that tell us? People are using them for essential trips. So much for scooters just being used for recreation. Johns Hopkins Hospital is the most popular block in the city right now.”

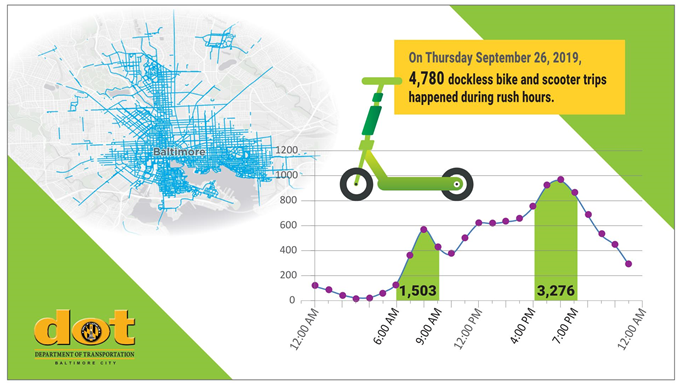

Even prior to COVID-19, Meg cited evidence that scooters were being used for essential trips, such as commuting.

“Just looking at the ridership data, there was a peak from 7-9am, a little bit of activity at lunchtime, then ridership would go up steadily in the afternoon. I began pointing to those numbers to demonstrate that people were using scooters to commute. Now when people are ONLY taking essential trips, we have additional reason to believe that’s the case. Seeing that people are taking them to the hospital and to food distribution sites solidifies this as a legitimate option for people.”

Image Courtesy of Baltimore DOT.

Photo by Elvert Barnes on Flickr.

“I never want to say scooters have been solutions to huge problems,” adds Meg. “It’s another mode people can choose. We have a high percentage of households without access to vehicles. I think it’s an option when people need one.”

The Future of Baltimore’s Dockless Vehicle Program

While the data indicates that scooters are a viable option for commuting and essential trips in Baltimore – both before and during COVID-19 – even if they don’t stick around forever, Meg wants to see the data and learnings from this program benefit everyone on the roadway.

“We need to consider alternative forms moving forward: the types of street typologies that give everyone a safe option. It doesn’t matter if it’s an e-scooter or a mode I haven’t even thought of yet, the rollout of ‘the next thing’ will go more smoothly if we accommodate different needs on different streets,” she says.

Meg also notes that scooter data is helpful for evaluating bike trips, because same level of data isn’t available for bikes. Some of the fees paid by scooter companies goes toward facility maintenance, which can be used toward protected bike lanes, a need that has been voiced by the Baltimore community.

The results of surveys distributed citywide and subsequently targeted to scooter riders indicate that first and foremost, people are looking for safer places to ride. In a response to the question “How could the program be improved?” the number one response was “more bike lanes,” and another commonly selected answer was “making existing bike lanes safer/more comfortable.”

“It’s about changing the self-fulfilling prophecy,” says Ethan. “By improving multi-modal infrastructure, you’re creating space for vulnerable roadway users, which can then lead to bike and scooter usage taking off in those areas.”

“A good example in Baltimore is Covington Street, a street that runs parallel to Key Highway, a four-lane arterial. Due to lack of a better option, people were riding bikes and scooters on the arterial. After we installed protected infrastructure along Covington Street, the proportion of rides on the arterial decreased and the share of rides on Covington Street increased. That’s the self-fulfilling prophecy we want to see.”

Advice for Other Cities Evaluating E-Scooter Programs

Meg says her biggest takeaway so far is to talk to as many people as possible, including other cities.

“None of our decisions have been made in a silo. I can’t have my eyes on everything in Baltimore. And there are other cities going through the same thing – so call a city that has similarities to yours, or that you look up to. In Baltimore, we’re constantly talking with nearby cities like DC and Philadelphia.”

Meg says resources that have helped her include case studies, the NACTO listserv, and the North American Bikeshare Association.

“Just know that right now nobody has the answers. But the conversations are happening. Use all the resources you can and reach out to other cities. If a dockless vehicle program is new to your city, there will be backlash and your boss or the mayor may say, ‘Do we want to take this chance? What’s another city doing?’ So gather all the information you can.”

Continue The Conversation

This is a topic that’s changing all the time. To learn more about Baltimore’s program or talk further about any of the data reported in this article, you can reach out to Ethan here.