May 16, 2023

In October 2016, a Seattle suburb welcomed, in the space of two converted tennis courts, a new little world: the White Center Bike Playground, where children could practice walking, biking, or rolling on a whimsical, colorful roadscape free from the unpredictable stressors of actual streets.

The White Center Bike Playground in Seattle. Photo credit: King County Parks.

This “traffic garden” attracted significant industry attention at its opening, with some writeups proclaiming a Danish ethos had crossed over into U.S. traffic education. However, while traffic gardens are popular tools for roadway safety and education in Denmark, the truth of the matter is that the United States also has a long history with the traffic garden-an idea that may be a uniquely appropriate tool for addressing traffic problems in America’s current transportation landscape.

In honor of National Safety Month, this article explores the history of the traffic garden in America, as well as its potential to improve American traffic safety outcomes. We’ll also tell you about an upcoming guide, “One Traffic Garden at a Time,” which will offer standardized guidance on designing, installing, and maintaining community traffic gardens. We believe this standardization can go a long way in addressing worrisome, entrenched trends in U.S. traffic culture.

Children at Play: Where Did the Traffic Garden Come From?

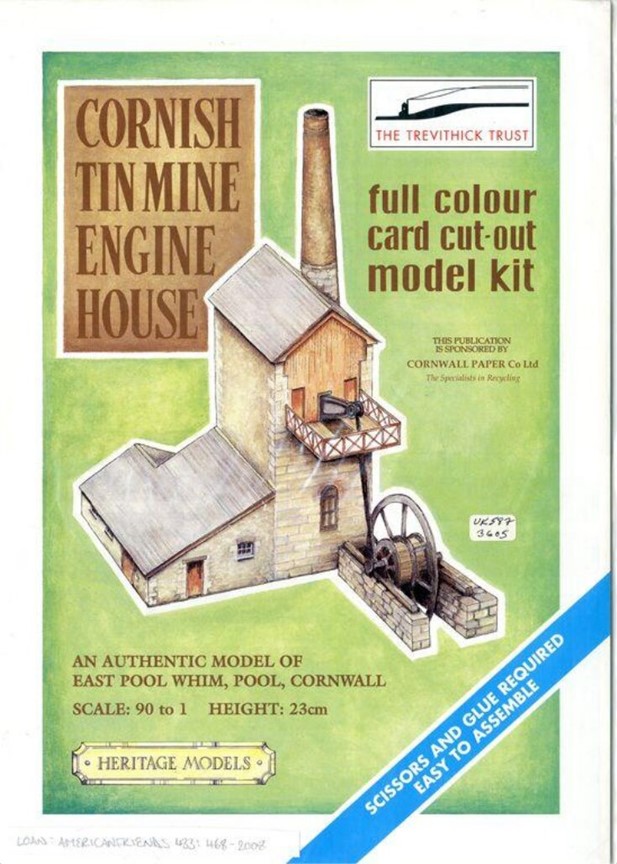

Although traffic gardens are new to many American communities, its grounding concepts are not. In fact, we inherited the traffic garden from a longstanding tendency to miniaturize cities for childhood imagination, play, learning, and safety. London’s V&A Museum of Childhood, which houses a collection of more than 12,000 paper models, suggests that the first commercially available paper model kits appeared in France as early as 1800; the Milton Bradley “Villages” set was among the most popular of paper model kits at the turn of the twentieth century.

Although traffic gardens are new to many American communities, its grounding concepts are not. In fact, we inherited the traffic garden from a longstanding tendency to miniaturize cities for childhood imagination, play, learning, and safety. London’s V&A Museum of Childhood, which houses a collection of more than 12,000 paper models, suggests that the first commercially available paper model kits appeared in France as early as 1800; the Milton Bradley “Villages” set was among the most popular of paper model kits at the turn of the twentieth century.

The enduring fascination children have with these imitation cities has a foundation in psychology and child development. Model cities familiarize children with their environments while also tidying away the elements that can make them feel threatening. A model village allows the child to exercise control over the village’s configuration, exploring their sanitized city without ever getting lost.

Image: a more modern example of a paper model. Source: V&A Museum of Childhood.

Children have also shaped the development of real cities, though less obviously or consciously. In the 1920s, the proliferation of the household automobile in the U.S. and U.K. fundamentally reorganized how people related to the spaces they inhabited, creating along the way new social concerns around transportation etiquette and safety. Children attracted special concern in (and exerted special influence on) this conversation: in 1924, the Ford Motor Company produced the short silent film “The Road to Happiness,” in which paved roads ease the muddy, waterlogged burden of the rural child’s commute to school. With class in session, the teacher reminds her students that they can win a four-year college scholarship in a traffic essay contest. A student wonders, “How are we going to write an essay on that subject when we haven’t a single good road in our community?”

The film’s argument surpasses the stance that roads improve a child’s access to educational opportunities; it argues instead that exposure to paved roads actually improves a child’s educational outlook by modernizing their perspective, fundamentally linking youthly upward mobility with the architecture of the motor age despite the fact that this architecture often posed physical danger to children. In 1921, 1,024 children were killed in traffic accidents in New York City. (Meanwhile, there were 16 child roadway fatalities in New York City in 2022.)

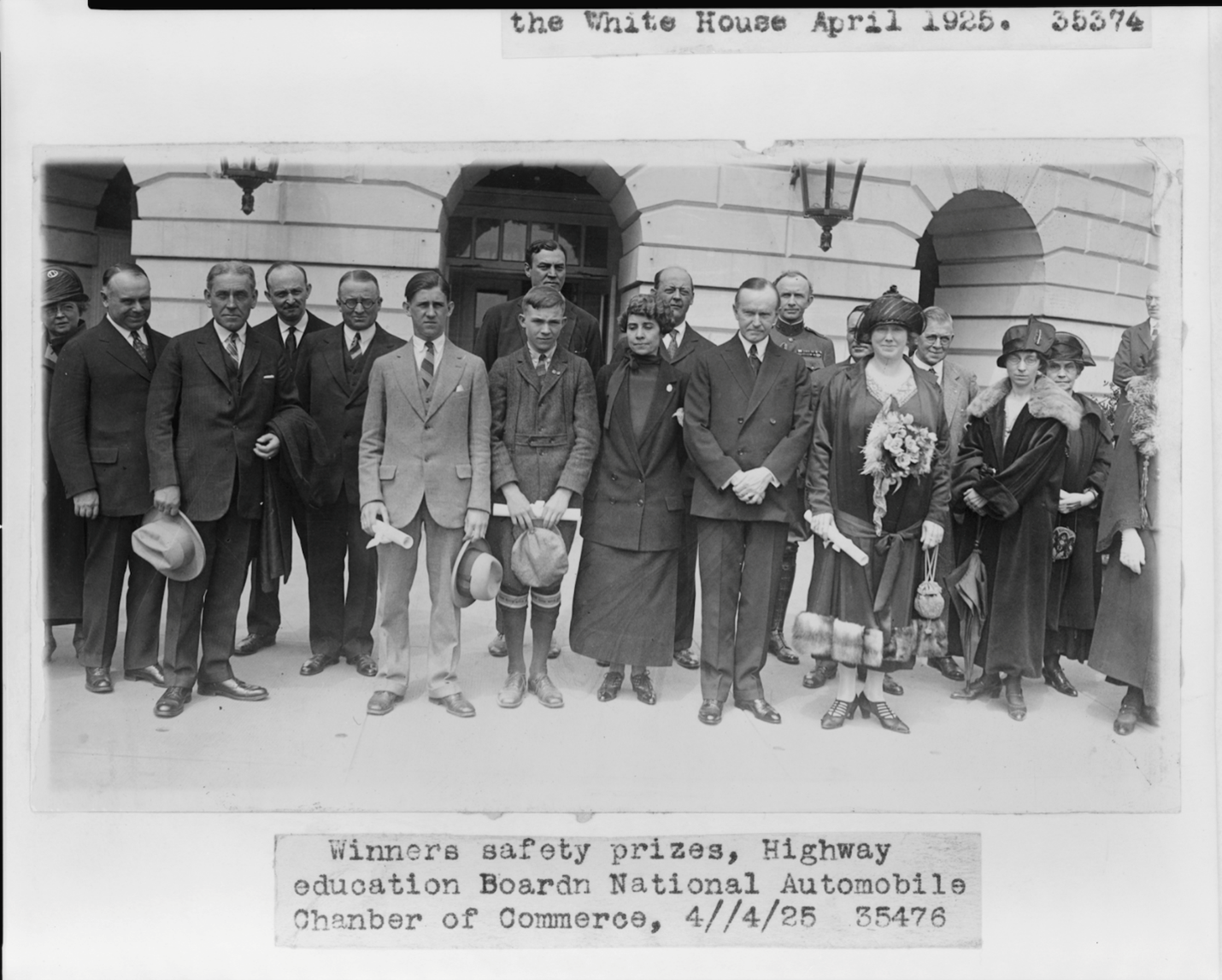

School essay contests encouraged young people to think about how they influenced traffic – and in the process may have overemphasized the power of the pedestrian.

Child roadway fatalities spiked during this period in part because the logic of traffic safety changed in favor of the automobile. In his book Fighting Traffic, historian and academic Peter D. Norton examines the public and private efforts that paved the way for the primacy of the automobile in America, writing that automobile manufacturers and interest groups collectively advocated to “reconstruct the safety problem so that pedestrians-“including children-“would bear substantial responsibility for their own safety.” These same interest groups sponsored grade school-level essay contests focusing on the importance of pedestrian conduct to traffic safety (like the contest mentioned in “The Road to Happiness”) and downplayed the role of driver conduct in the press. Collectively, these examples can help us understand how the relationship between automobiles and children was strained from its earliest days: children were cited as the justification for making long-term transportation investments that prioritized the automobile, even as they were largely left to defend themselves once put in danger by it.

In light of the skyrocketing danger posed to the children who dared to step foot on the road in the early twentieth century, it makes sense that child traffic safety education would find its way off the essay page and into a more child-friendly vehicle: the model city. In 1937, in response to another child traffic fatality, Ohio police officer Fred Boals created the first U.S. “Safety Town“, a child-sized city designed to promote traffic safety awareness and modality skill. By 1964, another Ohioan, Dorothy Chlad, formed the National Safety Town Center.

A safety town in Mansfield, Ohio. Photo credit: Richland Source.

These safety towns grew in their programming to include lessons on police interactions and fire safety, and could be quite elaborate in their constructions, sometimes possessing real streets and electricity. An early safety town in the U.K. featured nearly two miles of simulated roadways, pedal-powered cars, and a superintendent who would hand out traffic “tickets.” However, this safety town and others like it couldn’t keep up with the extreme maintenance required, creating a need for a comparable educational tool that required less in the way of permits and community oversight.

The Traffic Garden Era

While the traffic garden and safety towns may sound like the same thing, the traffic garden’s comparable simplicity to the safety town makes it a more efficient, flexible, and democratic educational tool.

With safety towns, the artistry and dedication to making the town look real, while showstopping, can make these projects significantly more difficult to pull off on technical, financial, and administrative levels. In contrast, the traffic garden’s use of surface-applied paints and minimal freestanding 3-D elements reduce administrative friction and cut down on cost while still igniting the imagination. The relative ease and low cost of the traffic garden make it a viable option to any community that has volunteers, a vision, and an empty asphalt lot.

Sabal Palm Bike Park in Tallahassee, Florida. Photo credit: Knight Creative Communities Institute.

As a silver lining, the supremacy of the automobile in America has produced plenty of vacant, unused asphalt lots. In a certain sense, our upcoming guide on traffic gardens, “One Traffic Garden at a Time,” could only exist in a country like America, as it builds on a growing community enthusiasm to leverage roadway and parking space overbuilt during the motor age to promote the safety of people walking, biking, and rolling.

A Guide That Supports and Standardizes the Installation of Traffic Gardens

“One Traffic Garden at a Time,” a collaboration between Arlington and Prince George’s Counties and funded by a grant from the National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board, breaks down the traffic garden project into three major phases: planning, implementation, and maintenance. There are several sub steps within each phase (including finding an appropriate community site, designing the garden and selecting the materials, installing the garden, and launching and maintaining the garden as a public amenity), and the guide is structured to make it easy for readers to go step-by-step or jump to the topics they need most assistance on.

The guide also assists project teams who may want support determining how a traffic garden could best serve their community. The guide identifies four types of traffic gardens, each with different community opportunities and needs:

Fixed traffic gardens include:

- Permanent traffic gardens use long-lasting, durable materials to repurpose an asphalt lot into a fixture of community beautification, play, and learning. Their constancy means that project teams can combine 2-D and 3-D elements (like street signs) more freely than traffic gardens that are designed to move between spaces or to only last in a space for a finite period of time. Collaborating with existing community organizations can be a helpful way of locating a site – schools, churches, or local businesses may have existing lot space they’d love to see transformed into a colorful, active hub. Although community volunteers can perform some aspects of the installation, the specialized nature of durable materials means that permanent traffic gardens are better installed by hired professionals. As such, permanent traffic gardens are often the most costly project type.

A permanent traffic garden that we helped to create in Alexandria, VA. Traffic gardens can rehabilitate underused spaces all throughout urban communities.

- Temporary traffic gardens are intended to create community space in the same way as their permanent counterparts, but perhaps only for a specific period of time, like summer break. They use materials that typically last between two and six months. They can typically be installed primarily by volunteer teams, and can give a community a chance to try out a traffic garden before committing to one.

Volunteers collaborating to install a temporary traffic garden. These gardens use surface-applied materials that have a shorter lifespan than those used for their permanent counterparts.

Meanwhile, mobile traffic gardens include:

- Pop-up traffic gardens are designed for specific community events like fairs, bike rodeos, or even a simple, freestanding demonstration. The materials are designed to last for a few hours to a few days. Because they’re often deployed as part of a larger event, it’s important to coordinate with event staff on how the context of the event may inform the design of the pop-up garden.

- Mobile traffic garden kits, which reduce the traffic garden down to only its most essential, most portable features, are great for the on-the-go educator. These kits can be deployed for single demonstrations and then repacked, meaning that many schools and recreation centers can act as a host site for a traffic garden.

A key takeaway in the guide is that the traffic garden that best suits one community may not suit another. For this reason, the guide ushers readers through a customizable project framework that provides teams with the structure they need to complete a project and the freedom they desire to make that project truly reflect their community. Additionally, traffic gardens, although deep-rooted in some ways in American transportation culture, are still underseen and underrecognized, and as such are often not listed as eligible for various project grants. The guide seeks to be an authoritative reference on sources for eligible funds.

Why Standardize Play?

Are traffic gardens too cutesy to effect any serious change in traffic education? Or even worse, do they perpetuate the harmful logic of the high motor age, reinforcing the burden of traffic safety on the child?

In actuality, the traffic garden presents a departure from the twentieth-century American attitude toward traffic safety education. Traffic gardens are intended to be public amenities that are operated by the community; they represent a shift away from the thinking that individual pedestrians are responsible for their safety and toward a shared responsibility for pedestrian safety. What’s more, although children can practice individually in traffic gardens, these spaces are also natural host sites for after-school programs, physical education programs, Safe Streets for All programs, bike rodeos, and any other group-based learning program.

Community-level investment in traffic education is needed now more than ever.

Community-level investment in traffic education has long been missing from American transportation culture, but it’s uniquely needed now: although child pedestrian fatalities are no longer at their astronomical 1920 levels, traffic deaths generally remain a tenacious American problem, and what’s more, some indicators suggest that U.S. children are losing certain transportation literacies, with the rates of daily child bicycling dropping 55% between 2001 and 2017. Traffic gardens offer an opportunity for children to develop these skills while simultaneously building an understanding of community investment in the idea of active transportation.

This guide has potential to inform the planning discipline, as well. The formalized guidance of traffic gardens offered in “One Traffic Garden at a Time” means that practitioners and researchers will have access to a greater (and more standardized) area data set for study. By creating a culture of interconnected traffic gardens in the Mid-Atlantic, we can better track how these gardens shape the development of children over the long term and develop important benchmarks that can inform the traffic education of future generations.

Ultimately, the traffic garden has the potential to transform both how children learn to move in traffic and how adults think about children as individuals with agency over their mobility. In a country characterized by its reliability on cars, we tend to consider the mobility of the under-16 crowd prescriptively (what does my child need to know in order to walk to and from school?) rather than discursively (how could teaching my child to assume agency over their mobility transform their lives and our communities?). Like any model city, the traffic garden represents an ideal reality of the communities we already live in: a space where generations of children can grow into a belief that child safety-indeed, the safety of anyone walking, bicycling, or rolling-is not just of public concern but of public asset.

Here at Kittelson, we’re interested in creative and vibrant communities that balance the modal needs of all people, and it’s our honor to support projects that further this goal, like the “One Traffic Garden at a Time” guide. We worked closely on the guide – and on this article – with Fionnuala Quinn, a civil engineer and subject matter expert in traffic gardens based out of Virginia. Quinn is the director of Traffic Gardens, an organization dedicated to traffic education and to empowering communities with the tools they need to walk, bike, and roll safely. Feel free to reach out to us to discuss traffic gardens further, and be sure to visit the Traffic Gardens site for more traffic garden pictures, projects, and information.