August 29, 2022

The rise of e-bike ridership across American cities-from Portland, to Chicago, to Washington, D.C.-pits a history of American transportation decision-making against the prospects of a newly popularized technology. How can the e-bike be a force for transportation justice?

First, let’s start with the definition of transportation justice, which refers to equal access for all people to receive the transportation they need for a better quality of life in a way that is affordable, reliable, safe, and connected.

Historically, practices like redlining, deceptive home lending practices, and indiscriminate highway development created division between communities. As a result, transportation investments for underserved communities have been lacking, which created separate transit realities for different communities. In many cases, the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified these service disparities.

Given these inequities, how can the e-bike be a force for transportation justice? E-bikes expand not only trip distances but also, in easing the strain of hills and heat, which trip types are possible. Expanded ranges benefit all riders-especially those who live in underserved or low-income neighborhoods, those without ready access to other vehicles or transit, and those who must travel further to reach essential resources, like workplaces and grocery stores. Many times, these characteristics overlap: people living in low-income communities are more likely to lack vehicle access and need to travel further to meet their daily needs.

The e-bike may offer a solution to some of these overlapping inequities caused by a long history of inequitable transportation decision-making. When deployed equitably, the e-bike can help connect underserved communities to larger transportation networks.

New Solution, New Problems

Although the e-bike has the potential to address access disparities, it won’t be a silver bullet. Certain features of the mode actually make it inherently exclusionary. To ensure e-bike implementation doesn’t deepen existing divides, agencies working toward equitable transportation infrastructure must address the following features:

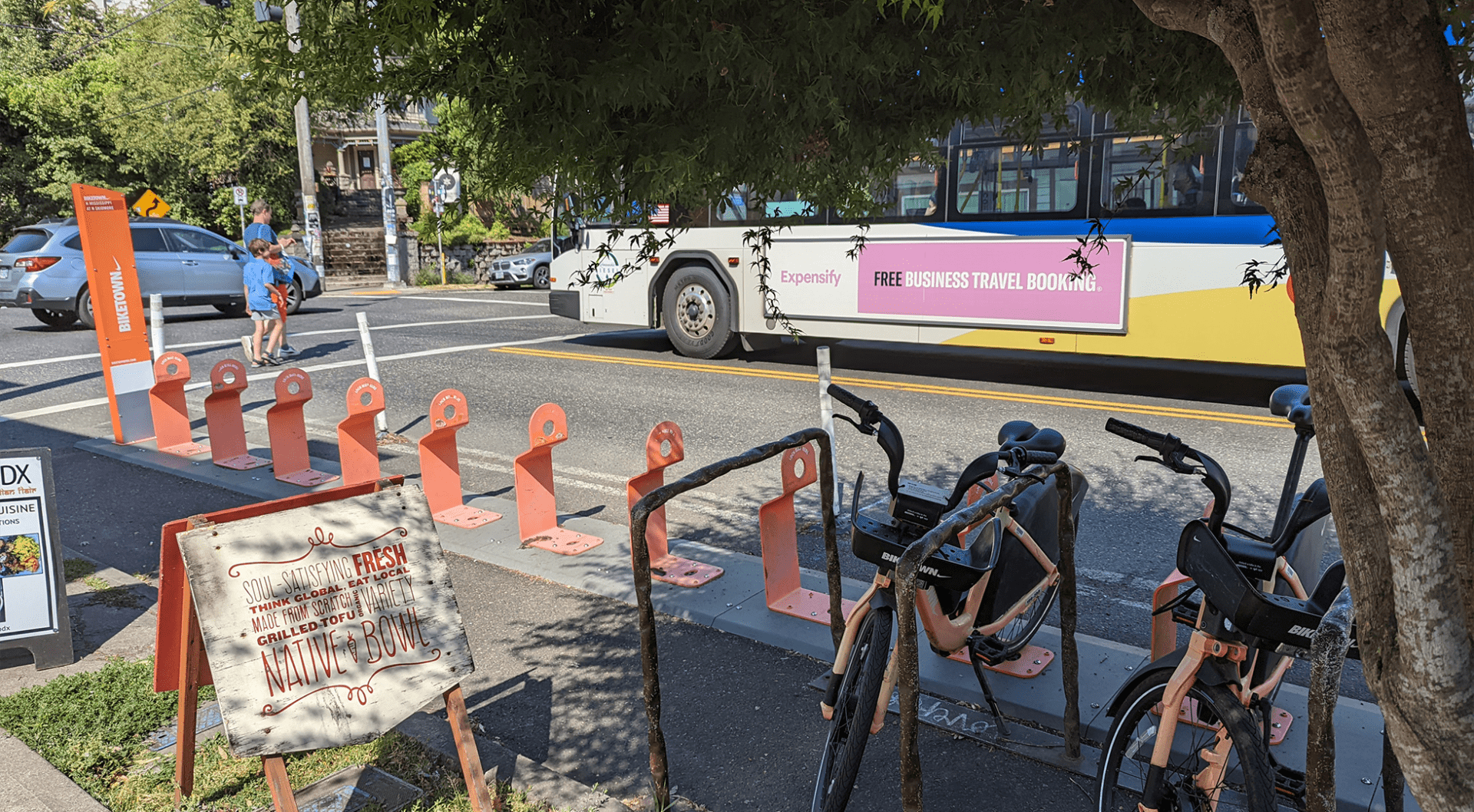

- The high cost barrier to buying or renting e-bikes. Purchasing an average e-bike can run anywhere from $1,000 to $7,600, according to a comparative study from Wired. Bikeshare programs are less expensive, but can still be cost prohibitive for people with low incomes. Biketown, the bikeshare program administered through Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) in conjunction with Lyft and Nike, charges an annual membership fee of $99, which breaks down to a single-ride fare of twenty cents per minute. Seattle’s bikeshare program charges 36¢ per minute; Chicago’s Divvy program charges 39¢ per minute; and New York City’s Citi Bike program charges $4 for the first 30 minutes, and then 23¢ for each minute after.

- The digital administration systems for bikeshare programs. Most bikeshare programs are administered digitally through an app. Users must be familiar with digital tools and apps and own a smartphone and credit card to participate.

- Fears or cultural stigmas about e-bikes and bicycling more broadly. Users may perceive silent barriers to using e-bikes, including anxiety about sharing roads with cars and feeling stigmatized by the connotation of poverty that riding a bicycle can carry in America’s car-centric culture.

- Lack of accommodation for people with disabilities. E-bikes cannot accommodate many people with disabilities, particularly those differences that prevent operating a two-wheeled bicycle.

- The weight of e-bikes. E-bikes are heavy, with most models weighing between 40 and 80 lbs. Because they are not easily carried, e-bikes may be restricted to individuals with secure ground-floor parking.

One of Biketown's bikeshare docks, with two e-bikes available for rides.

Additionally, certain operational practices in city bikeshare programs risk further exclusion of already disadvantaged communities:

- Docking station distribution. “Docked” bikeshare programs require riders to pick up and return e-bikes at designated sites around the city. For these programs to include underserved communities, including communities of color and lower-income communities, docking sites must be distributed widely throughout all neighborhoods-not just in the most heavily trafficked areas.

- E-bike distribution. To ensure docked systems have enough e-bikes for people to use, the bikes must be regularly redistributed across the city. But without dedicated staff to properly rebalance the bikes, a bikeshare’s most frequently used assets will inevitably accumulate in high-traffic areas, leaving them unavailable to people in outer neighborhoods who may need them the most. Issues dock scarcity and of unbalanced docks felled several bikeshare programs, including Seattle’s first, Pronto, in 2017.

- Dockless programs’ perimeters. Dockless bikeshares avoid the thorniest operational obstacles of docked systems by allowing riders to drop off rented bikes anywhere within a preestablished perimeter. However, in doing so, these programs quite literally exclude any people living outside of this perimeter. When it launched in 2016, Portland’s Biketown had a service area of predominantly White, affluent, central neighborhoods. Such coverage offered little benefit to residents in the city’s far eastern neighborhoods, who tend to be more disadvantaged when it comes to transportation access.

If shared micromobility programs are to help reform a transportation culture steeped in centuries of discriminatory practice, agencies will need to approach these exclusionary aspects of e-bikes and bikeshares carefully. The following approaches can help practitioners incorporate e-bikes while avoiding the pitfalls, ensuring the e-bike achieve its potential as a tool for transportation justice.

"Outreach is the most important step" for bikeshares looking to have a transformational impact on their communities, according to a 2019 study by Portland State University. Any bikeshare program cannot simply be for a community; it must be of the community it serves.

1. Work with community activist groups to address access gaps.

While e-bikes can expand mobility options within marginalized communities, simply placing e-bikes in those communities isn’t enough to dismantle the transportation barriers those communities face. “Outreach is the most important step” for bikeshares looking to have a transformational impact on their communities, according to a 2019 study by Portland State University. Any bikeshare program cannot simply be for a community; it must be of the community it serves.

After conversations with community activists in Portland, Biketown has added two appendage programs: Biketown For All and Adaptive Biketown. Both programs address gaps in the original service. Biketown For All reduces or eliminates membership costs for qualifying individuals, including people living in subsidized housing or who qualify for other social services. Adaptive Biketown launched in 2017 after feedback from Portland’s disabled community revealed the need for hand-powered, tandem, and electric-assist recumbent bicycles to better suit a range of bodies.

Chicago’s Equiticity, a community nonprofit dedicated to racial justice in transportation, provides a community bike library. The library also functions as a community gathering place and mobility hub for participants to build support systems. The nonprofit has also teamed up with Mobility Development Partners and Shared Mobility, Inc., to establish e-bike libraries throughout the US, according to a recent Equiticity newsletter. These collaborations have already produced free e-bike libraries in Pacoima, CA, and Buffalo, NY.

Part of Equiticity’s transformative place-making involves holding community mobility rituals in Black, Brown, and Indigenous neighborhoods. Often hosted in collaboration with Divvy and other neighborhood organizations, these events pursue racial justice in mobility by normalizing active transportation in communities historically failed by the American medical establishment; strengthening community relationships; and, most importantly, by challenging assumptions in the transportation planning process.

This last action is critical. In an interview with The Brake podcast, Equiticity’s president and CEO, Olatunji Oboi Reed, observes how transportation’s status quo has harmed Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities. He suggests that ownership over the transportation planning process should be returned to the neighborhood’s residents and community organizations. Ultimately, according to Oboi, it’s impossible to restructure an inequitable transportation network without stepping aside so that the people marginalized by that network can take charge of its restructuring.

Equiticity members, Olatunji Oboi Reed and Derek Brown, lead a community bike ride.

2. Enshrine equity measures in local and State transportation policy.

Policy also shapes how e-bikes can effect change over transportation’s entrenched inequities. To address the continued access inequity of Biketown, PBOT expanded the service perimeter to more diverse and more underserved eastern neighborhoods in January 2022. Expansion in these areas wasn’t accidental or inevitable; it was the direct result of PBOT’s equity-focused policies, which include an Equity Committee and an Equity and Inclusion Officer who hold the bureau accountable to its most vulnerable residents.

State and local governments can also make the transportation landscape more equitable by subsidizing the purchase of e-bikes. California’s E-Bike Affordability Program seeks to distribute $10 million in e-bike rebates to help 10,000 California families purchase e-bikes. Depending on the program’s final design, up to 80% of these rebates could go toward low-income families. These rebates would effectively expand California’s Clean Vehicle Rebate Project (which currently offers rebates between $1,000 and $7,000 for the purchase of electric cars and scooters) to include e-bikes. These rebates would also apply statewide, as many California e-bike rebates today are hyperlocal. However, there are concerns that a perceived lack of interest in the modality has stalled progress on the program.

Denver, CO, offers e-bike incentives to promote environmentally sustainable transportation. The Denver Climate Action Rebate program offers a $400 rebate upon purchase of an e-bike and a $1,200 rebate to low-income families upon purchase of an e-bike. The entwined histories of climate injustice and racially inequitable housing means the program’s equity measure shouldn’t be viewed as a secondary “add-on” but rather as complimentary to its climate goal. A city can’t have climate justice without racial justice, and vice-versa. In addition to implementing rebate programs like those in California and Denver, states might also encourage e-bike use by levying a higher gas tax and putting its proceeds toward sustainable transportation.

Implementing buffered bicycle lanes reallocates street space to provide for multimodal travel, making bicycling safer and more appealing.

3. Pursue supportive physical and digital infrastructure for e-biking.

Increasing e-bike access to underserved communities can only create meaningful change if community streets are designed to integrate bicyclists into the traffic flow. Implementing buffered bicycle lanes reallocates street space to provide for multimodal travel, making bicycling safer and more appealing. Quick-build bicycle lanes, popularized during the COVID-19 pandemic, are a fast and cost-effective way to integrate e-bikers into traffic.

Bikeshare programs also need features that facilitate equitable administration. To overcome technological barriers to e-bike access, Seattle’s revamped its Lime bikeshare program to include a text-to-unlock feature for qualifying residents who might not have a smart phone or a credit card. Portland’s Biketown For All and Chicago’s Divvy for Everyone offer registration either in person or over the phone.

Moving Forward

E-bikes have the potential to dismantle longstanding barriers to transportation justice, but only if we first dismantle the barriers to the e-bike. Sustained dialogues with community activists should inform how shared micromobility programs can operate more equitably. Policy and infrastructure should elevate equity and make e-bikes available and useful for everyone. Together, these approaches can ensure the e-bike fulfills its promise to break, rather than reinforce, entrenched transportation inequities.

Here at Kittelson, we want to help change the transportation landscape in ways that address longstanding inequities rooted in race and class. Please reach out if you’d like to discuss the ideas in this article further!