January 19, 2021

The stories we tell have meaning. They inspire minds and quietly influence what we believe to be possible for us from a young age. As we reflect on Black History Month and our transportation industry, it is important to share the story of Garrett Morgan.

The stories we tell have meaning. They inspire minds and quietly influence what we believe to be possible for us from a young age. As we reflect on Black History Month and our transportation industry, it is important to share the story of Garrett Morgan.

Garrett Morgan was born during the Reconstruction era on March 4, 1877, in Claysville, Kentucky. His parents, Sydney Morgan and Elizabeth Reed, were both enslaved and eventually freed with the end of the Civil War. In addition to being the son of a freedman and freedwoman, Morgan was also part Native American. The achievements Morgan made as an inventor and engineer are even more remarkable when considering the injustices he faced as a mixed-race Black man living in the time of Jim Crow, an era of enforced racial segregation in America.

Like most Black children of his time, Morgan’s formal education was cut short by his family’s need to send him to work as soon as possible. His formal schooling ended in the sixth grade and he moved to Cincinnati at the age of 14 in search of employment. He spent the majority of his teenage years working as a repairperson and moved to Cleveland in 1895, where he began fixing sewing machines. Here Morgan found his passion for engineering. During this time, he developed his first invention – a belt fastener for sewing machines.

Morgan continued inventing in the early 20th century, with his successful enterprises propelling him to a position of leadership in his community. Morgan’s identity as a Black man was also inextricably linked to his commitment to civic leadership. He was a member of the newly formed NAACP, was active in the Cleveland Association of Colored Men, donated to Black colleges and opened an all-Black country club. In 1920, he launched the African American newspaper the Cleveland Call, which was later named the Call and Post. Morgan was a leader in the community, as well as an engineer.

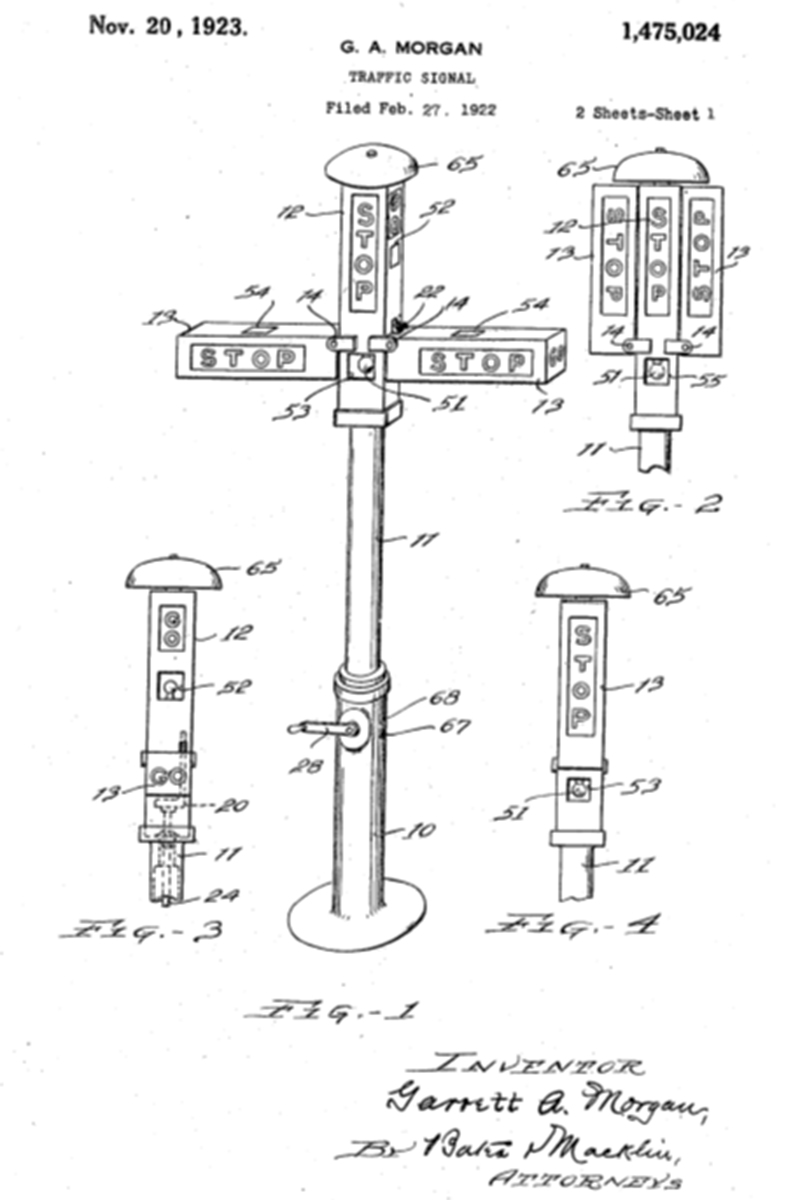

Morgan was prosperous enough to have a car by the 1920s and like so many of us engineers today, experienced firsthand the importance of ensuring people could travel safely and efficiently. The American street was undergoing chaotic change at the time: bicycles, horse-drawn buggies, streetcars, and pedestrians all jockeyed for space on Cleveland’s narrow streets. Morgan saw many of the same multi-modal challenges we still grapple with today. After witnessing a crash between a car and horse buggy, Morgan noticed something that is now fundamental to signal design: traffic signals needed an interval between ‘red’ and ‘green’ so people had time to react. Thus, the ‘yellow’ interval was born.

At the time, Cleveland’s traffic signals were manually operated so Morgan designed and patented America’s first three-position signal. On November 20, 1923, the US Patent Office granted Patent No. 1475074, cementing Morgan’s place in history.

This accomplishment proved bittersweet, as he sold his patent to General Electric for $40,000 thinking that few people would do business with a Black man. General Electric went on to profit off the installation of three-position signals in cities across the county. Despite the injustice he faced, Garrett Morgan’s legacy lives on in every signal we plan, design, and use.

This accomplishment proved bittersweet, as he sold his patent to General Electric for $40,000 thinking that few people would do business with a Black man. General Electric went on to profit off the installation of three-position signals in cities across the county. Despite the injustice he faced, Garrett Morgan’s legacy lives on in every signal we plan, design, and use.

Morgan’s story reminds us of many traits we value professionally: lifelong learning, passionate work ethic, innovative thinking, people-centric solutions, and community leadership. This month we highlight Morgan for the values he held and his contributions to our industry. More than that, we hope reflecting on Morgan’s story will resonate with readers from different walks of life. Whether it be those who take pride in seeing an exemplary leader finally celebrated for his contributions. Those trying to gain a greater understanding for how a lived experience does (and does not) differ from their own. Or, yes, those young minds looking to history book heroes for inspiration. We hope you will tell Morgan’s story and live his example because his story has meaning.

Other Black Transportation Innovators

As we researched Garrett Morgan, we found dozens of other inventors and innovators, their stories all engrossing. And this is only a brief summary. We strongly encourage you to look up these names and learn more.

Inventors Who Began Life as Slaves

Andrew Jackson Beard

- Born a slave on a plantation in Woodland, Alabama and spent his first 15 years there (until emancipation).

- Injured in rail car coupling accident

- Patented the Jenny Coupler, which automatically joined rail cars by allowing them to bump into each other, eliminating the dangerous job of manually connecting train cars

- President Benjamin Harrison subsequently signed the Safety Appliance Act, which made automatic couplers and air brakes mandatory on all trains

Horace King

- Born a slave, freed in 1846

- Became one of the most respected bridge builders in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi during the nineteenth century

- Represented Russell County in the Alabama legislature, 1868-1872

Charles Richard Patterson

- Blacksmith who escaped from slavery in Virginia

- Opened a business building horse-drawn vehicles

- The Patterson family manufactured their first Patterson-Greenfield car in 1915

- The Patterson family manufactured motorized vehicles well into the late 1930s

Pioneering Women

Bessie Coleman

- First Black American female pilot

- Taught other black women to fly, gave lectures and performed at flying exhibitions

- Daughter of a sharecropper, grew up in Waxahachie, TX, helping her mother pick cotton and wash laundry to earn extra money

- By the time she was eighteen, she saved enough money to attend the Colored Agricultural and Normal University (now Langston University) in Langston, Oklahoma, but dropped out after only one semester because she could not afford to attend

- Her brothers, who served in the military during World War I, teased her because French women were allowed to learn how to fly airplanes and Bessie could not.

- She applied to many flight schools across the country, but no school would take her because she was both Black and a woman

- Famous African American newspaper publisher, Robert Abbott told her to move to France where she could learn how to fly. She began taking French classes at night because her application to flight schools needed to be written in French.

- Received her international pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

- Coleman’s dream was to own a plane and to open her own flight school. She gave speeches and showed films of her air tricks in churches, theaters, and schools to earn money.

- She refused to speak anywhere that was segregated or discriminated against Black people.

- In 1922, performed the first public flight by a Black woman.

Lois Cooper

- First Black American transportation engineer hired by the Engineering Department at California’s Division of Highways, now known as Caltrans (1953).

- First Black woman in California to pass the PE License Exam

- Started out as an engineering aide and worked her way up to transportation engineer and project manager

- Major projects included the I-105 Century Freeway, the San Diego Freeway, Long Beach Freeway, San Gabriel River Freeway, and Riverside Freeway

- First woman director of the First Diamond Lane, the predecessor to carpool lanes

Maya Angelou

- American poet, memoirist, and civil rights activist.

- Published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, several books of poetry, and is credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning over 50 years.

- Received dozens of awards and more than 50 honorary degrees.

- San Francisco’s first Black female streetcar conductor, at just 16.

- She got the job after her mother encouraged her to keep going back until they let her apply.

Men of Many Talents

Richard Spikes

- Barber, schoolteacher, bartender, violinist and inventor

- Shortly after his marriage, he became dissatisfied with how draft beer was dispensed from a keg. He developed variations on the pressure-dispense beer tap. The patent was purchased by the Milwaukee Brewing Company and variations of the invention are still in use

- Lifelong inventor, responsible for all the inventions listed here, the last one patented the year he died:

- Railroad semaphore (1906)

- Automatic car washer (1913)

- Automobile directional signals (1913)

- Continuous contact trolley pole (1919)

- Improved automatic gear shift (1932)

- Transmission and shifting thereof (1933)

- Automatic safety brake (1962)

Meredith Gourdine

- Olympic silver medalist in long jump, Helsinki 1952

- Father was a janitor–told him “If you don’t want to be a laborer all your life, stay in school.” He graduated from Cornell and opened his own research laboratory

- Went on to develop an exhaust purification system for cars in 1967 that is now referred to as the catalytic converter

- Biggest creation was the Incineraid system, which was used to disperse smoke from burning buildings and could be used to disperse fog on airport runways. It worked by negatively charging smoke or fog, electromagnetically charging the airborne particles so they would fall to the ground.

- Received patents for the Focus Flow Heat Sink, which was used to cool computer chips and for processes for desalinating sea water, for developing acoustic imaging, and for a high-powered industrial paint spray.

- Held over 30 patents.

- Served on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Advisory Panel on Energy

- Was inducted into the Engineering and Science Hall of Fame in 1994.

Granville T. Woods

- Often referred to as the “Black Thomas Edison”

- Denied opportunities and promotions because of the color of his skin, he formed the Woods Railway Telegraph Company in 1884 with his brother, Lyates

- Had difficulty enjoying his success because other inventors frequently made claims to his devices

- For example, Thomas Edison said he had first created a similar telegraph to Woods’ and was entitled to the patent for the device. Woods was twice successful in defending himself against Edison’s claim

- Many of Woods’ later inventions increased efficiency and safety in railroad cars

- Created a method of supplying electricity to a train without any exposed wires or secondary batteries

- Developed the third rail concept allowing a train to receive more electricity while also encountering less friction

- Obtained more than 60 patents for inventions including an automatic brake and for improvements to other inventions