December 15, 2021

Around the turn of the nineteenth century in American cities, horses provided nearly all motive power. They pulled streetcars, lugged market goods, delivered milk and coal, drew carriages, carried riders, towed canal boats, and hauled fire engines. Their bodies and daily needs set expectations about what a city was and how its streets should be used.

Too often, horse-powered transportation is written off as a quaint curiosity of a vague past, sometime “back in the day.” But the history of urban horses matters a great deal and holds valuable information for planners and engineers in the present. Understanding a community’s horse-powered past can reveal a footprint designed for the very low-speed, complete street environment we work so hard to create today.

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2001-008.50. 1914. Portland's horses helped set the grades, curvature, and paving of the city's streets. Here, two horses help repair NW Maywood Drive, which is today part of the Kings Heights neighborhood. Anyone familiar with Portland's streets will recognize the ring to the lower right. While many of these rings were removed over time, today the City of Portland ensures these important relics of our horse-drawn past are preserved.

Horses and the Built Environment

Horses have had a tremendous influence on the form and function of the built environment. Their housing requirements and enormous appetites meant the urban landscape was filled with stables, many of which were multistory to accommodate hundreds of horses plus great quantities of hay and grain, vehicles, and shoeing facilities.

Many of the staple features of today’s transportation systems also have roots in horse-powered transportation. Here are just a few:

Pavement Materials. On the street, balancing the conflicting needs of hoof and wheel dictated pavement materials. Wheels needed hard and smooth surfaces for easing turning, but hooves needed coarse and elastic surfaces for traction and joint relief. Finding a surface with sufficient traction but low resistance was a challenge. Prior to paving, roads were highly seasonal: hard and dusty in summers, wet and mucky in fall and spring. Colder climates also fought snow and ice. Wet roads sucked hooves down, absorbing energy and creating draft. Roads that were too smooth lacked traction. Roads that were too hard didn’t lessen draft.

Nineteenth-century innovations helped improve road systems. In 1820, John McAdam invented a method of packing dry layers of different sizes of broken stone (aptly called “macadam”). Stone size was key. On the top level, stones no larger ¾-1 inch in diameter better distributed the weight of carriages, helped with horse mobility, made turning easier, and helped to prevent ruts as smoothing over the small stones was easy to maintain. And by keeping the road as level as possible, the finer stone particulate sent run-off (as well as trash and horse waste) into adjacent ditches.

Transit Stops. Prior to the early 1870s, streetcars and omnibuses stopped when hailed, regardless of where the passenger stood. The constant and unpredictable starting and stopping was hard on horses’ legs. To save wear and tear on the living motors, companies began stopping only at street corners to pick up passengers.

Speed Limits. Speed limits were originally set by horses’ natural gaits. With some breed exceptions, most horses walk, trot, canter, and gallop. A walk sets a pace of about 4 mph, a trot 8-12 mph, a canter at 10-17 mph, and a gallop at 25-30 mph. Most American cities set urban speed limits at a trotting pace and considered anything much over that at high risk of life and limb.

Redefining the City

The efficiency of the horsecar system fed city expansion. Prior to the industrial revolution, cities were necessarily small, confined to the distance a person could reasonably commute on foot. This limited radius made city neighborhoods more culturally and socially homogenous. By allowing people to live further from work, streetcars helped reorganize cities, creating early suburbs and putting distance between residential neighborhoods and business districts. The city pattern of radiating rings came in part from horsecar lines. In hilly cities like Boston and Pittsburgh, streetcar routes had to follow the path of least resistance, concentrating suburban development in valleys to avoid steep grades.

Horsecars even changed what streets were for. Prior to the proliferation of streetcars, streets were about much more than transportation-they were spaces for commerce, socializing, and recreation, according to historian Ann Norton Greene. The introduction of faster-moving vehicles began to alter the purpose of streets.

“Any kind of railway, with its fixed rails, encouraged through traffic and faster-moving vehicles,” argued Greene in her book Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America. “[This] redefined the street’s primary purpose as a transportation artery-a space to go through rather than a place to go to….” We often blame automobiles for the decline of community relationships and changing urban dynamics, but these developments go back much further to horse-powered transportation.

The Original Automated Vehicle

The equine mind has a knack for patterns and sense of direction. On popular night-routes, streetcar lines would often run their older, more experienced horses. Because the horse knew the way without someone in the driver’s seat, the operator could collect tickets without needing a second man as conductor. Because many horses knew the way home to the barn, some streetcar drivers would even catch up on sleep and nap while deadheading back to the stables.

Delivery services for bakeries, coal firms, ice companies, and dairies preferred horses to trucks well into the twentieth century. Well-trained and experienced horses could memorize their regular route, travelling from house to house automatically and waiting patiently as the driver carried loaves, crates, blocks, or bottles from the wagon to the front door. The benefits of these automated vehicles was not lost on early twentieth century workers, as horse-drawn delivery wagons persisted into the 1960s in some areas.

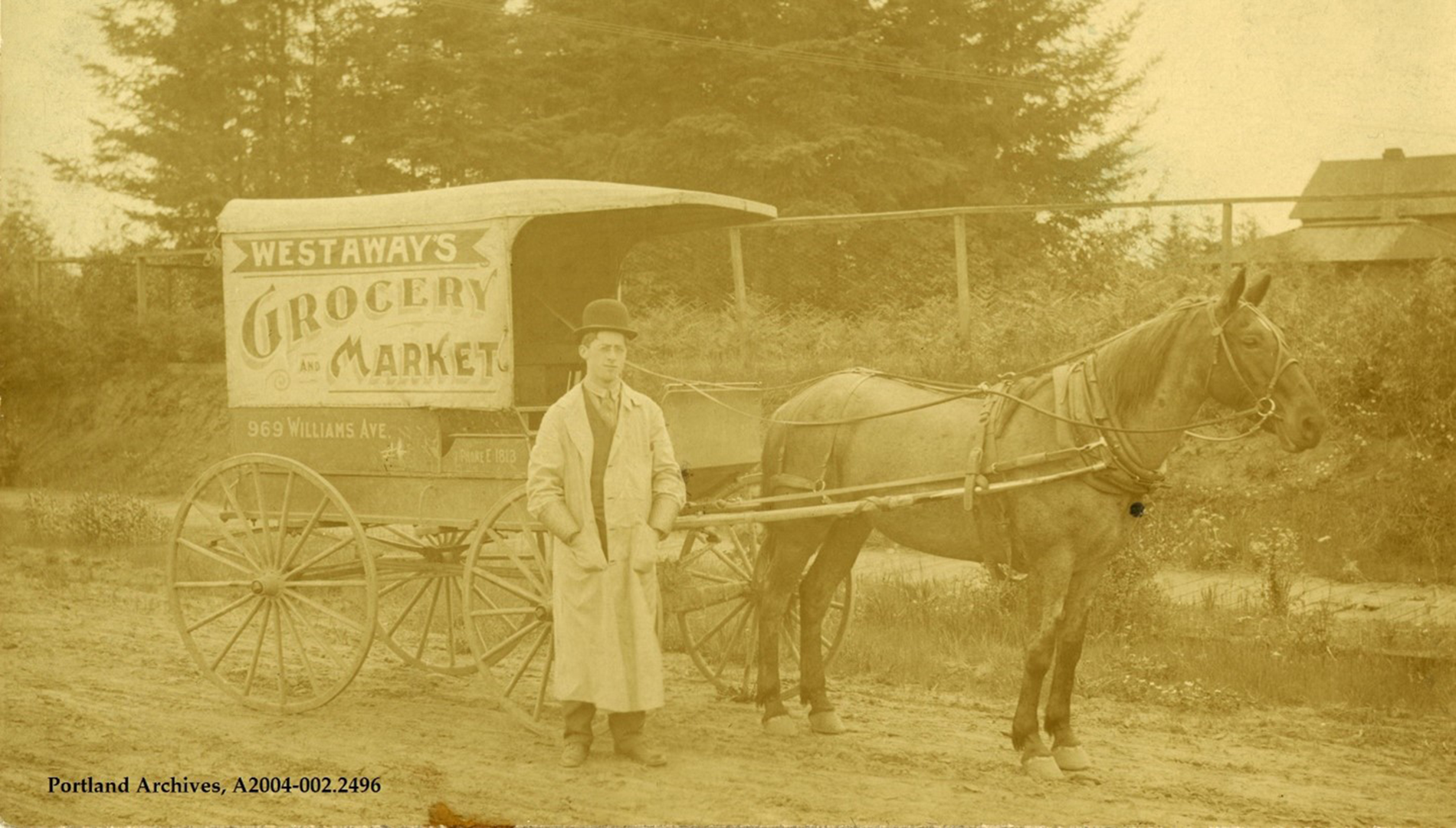

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2004-002.2496. 1909. While we can't know whether this Westaway's Grocery Market horse knew his route, we do know that equine brains have a keen sense of direction and knack for memorizing patterns. Many turn-of-the-century delivery drivers relied on their equine partners to make successful and efficient trips. With the horse stopping at each house or business, the driver was free to walk from cart to door, unloading the milk, coal, or other goods without having to clamber back into the driver's seat.

Horse-Powered Portland

Had Kittelson’s Portland office existed around the turn of the twentieth century, our commutes and workdays would look much different than they do today. For starters, we would be sharing our city with around 90,400 humans and more than 3,600 horses. (That’s one horse for every 25 humans, and nearly 100 horses per square mile.) Each day, these 3,600 horses would collectively generate upwards of 90 tons of manure and 3,600 gallons of urine.

To get to work, many of us would hop on a streetcar line, some electric but some still drawn by horses. Those of us heading out to a site visit might hail a horse-drawn cab called a hack. Clip-clopping out of town, we might pass the United Carriage Company’s considerable quarter-block livery, hay, and feed stable, which was located just around the corner at Broadway and Taylor.

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2004-002.1104. 1904. Early twentieth-century Portland streets saw great modal diversity-even as electrification increasingly replaced horsepower. Here, SW Third Ave teems with people walking and bicycling amongst horse-drawn wagons and streetcars.

As we travelled, our licensed and badged hack driver would be operating under strict rules of street conduct set by the City. Speed was capped at six miles per hour, and to cross any bridges or wharfs, as well as travel through any public parks or squares, the driver would have to bring the horse down to a walk. Drivers couldn’t stand hacks within ten feet of street crossings, more than two feet from sidewalks, and especially not in front of “No hack allowed to stand here” signs. And if we were travelling after dark, the hack must have lights.

The city also set standard fares and distances, measuring one standard mile with twenty city blocks. Fares were determined by the number of passengers, destination or trip purpose, as well as whether the cab was called on-demand or scheduled in advance. Perhaps most importantly, the City required our hack driver-and all drivers and handlers-to treat animals humanely.

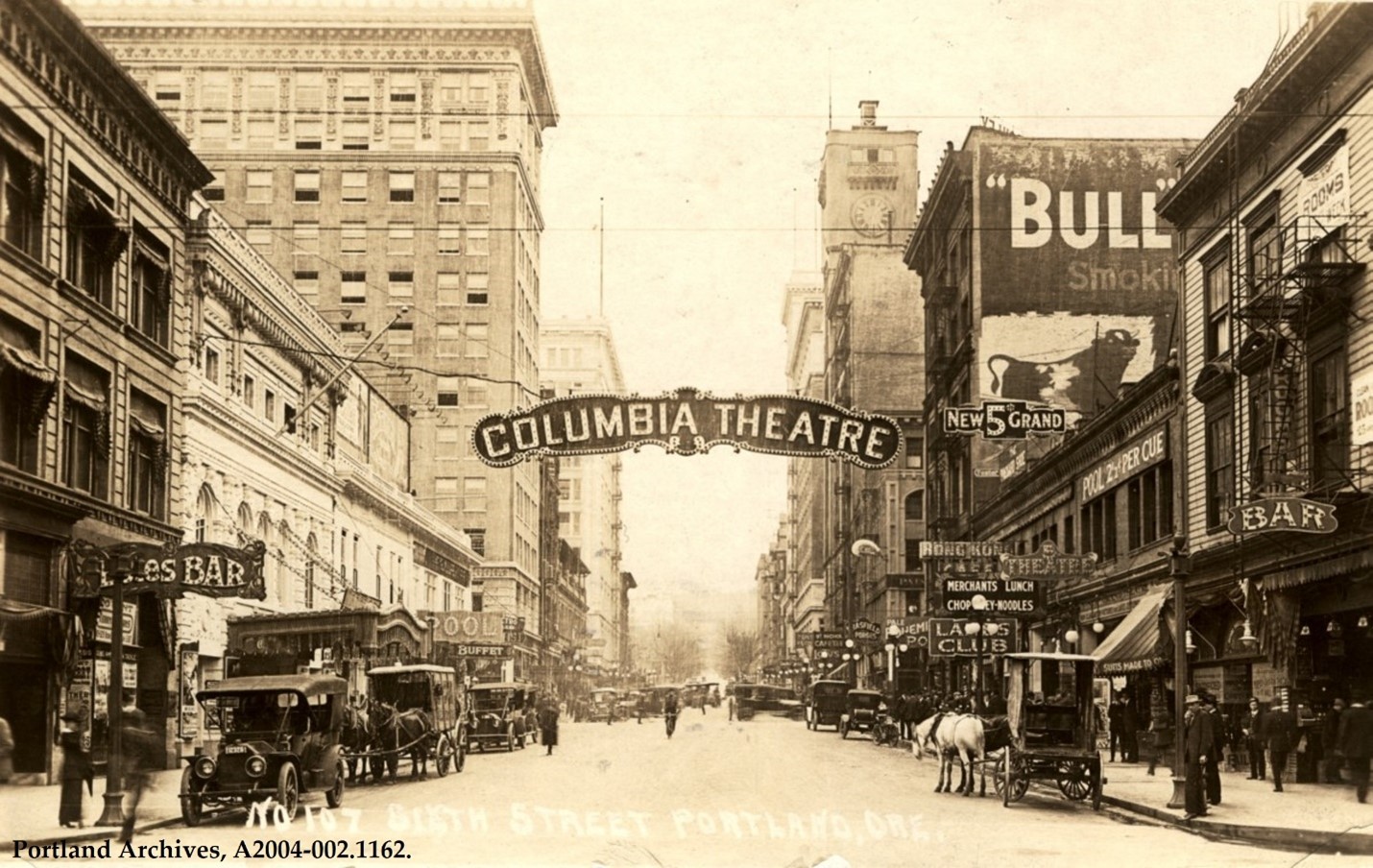

Those of us who remained in the office would look out across 6th Street to the Corbett House’s carriage house, stable, and hen yard or down on to the street teeming with horses, carriages, carts, street cars as well as people walking and bicycling. By 1917, this melee would regularly include automobiles.

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2004-002.1162. 1917. 1 SW 6th Ave, Portland, Oregon.

Anytime we travelled for personal or professional reasons in Portland, we would be subject to City ordinances that shaped who could use the streets for what purposes. City code preserved sidewalks for people and roads for travel. Horses could not be ridden, led, hitched, or driven on the sidewalk. To preserve the integrity of streets to not disrupt traffic, we could not feed a horse on any street improved by “macadamizing, planking to the width of fourteen feet or more, or by being paved with Nicholson or stone block pavement.” A fleet of City-owned street-sweeping horses would keep the streets clear.

Lessons for Tomorrow

Reconstructing a horse-powered Portland, or any community from the past, is more than a walk down memory lane. These exercises can offer valuable clues to the slow, connected urban environment we strive toward in planning and engineering today.

Because our urban areas and their transportation networks grew around horses, the foundation of many cities and urbanized communities remains set for the slow speeds set by a walk and trot. The footprint of a low-speed, largely walkable city supported by short to medium distance public transit was set by horses. Photographs and maps can help reconstruct this scale and reveal the ideal spacing and geometry that exists underneath modern cities. By peeling back these layers in the city palimpsest, we can look for ways of improving existing spaces.

Consider, for example, how horses influenced setbacks and sidewalk structures.

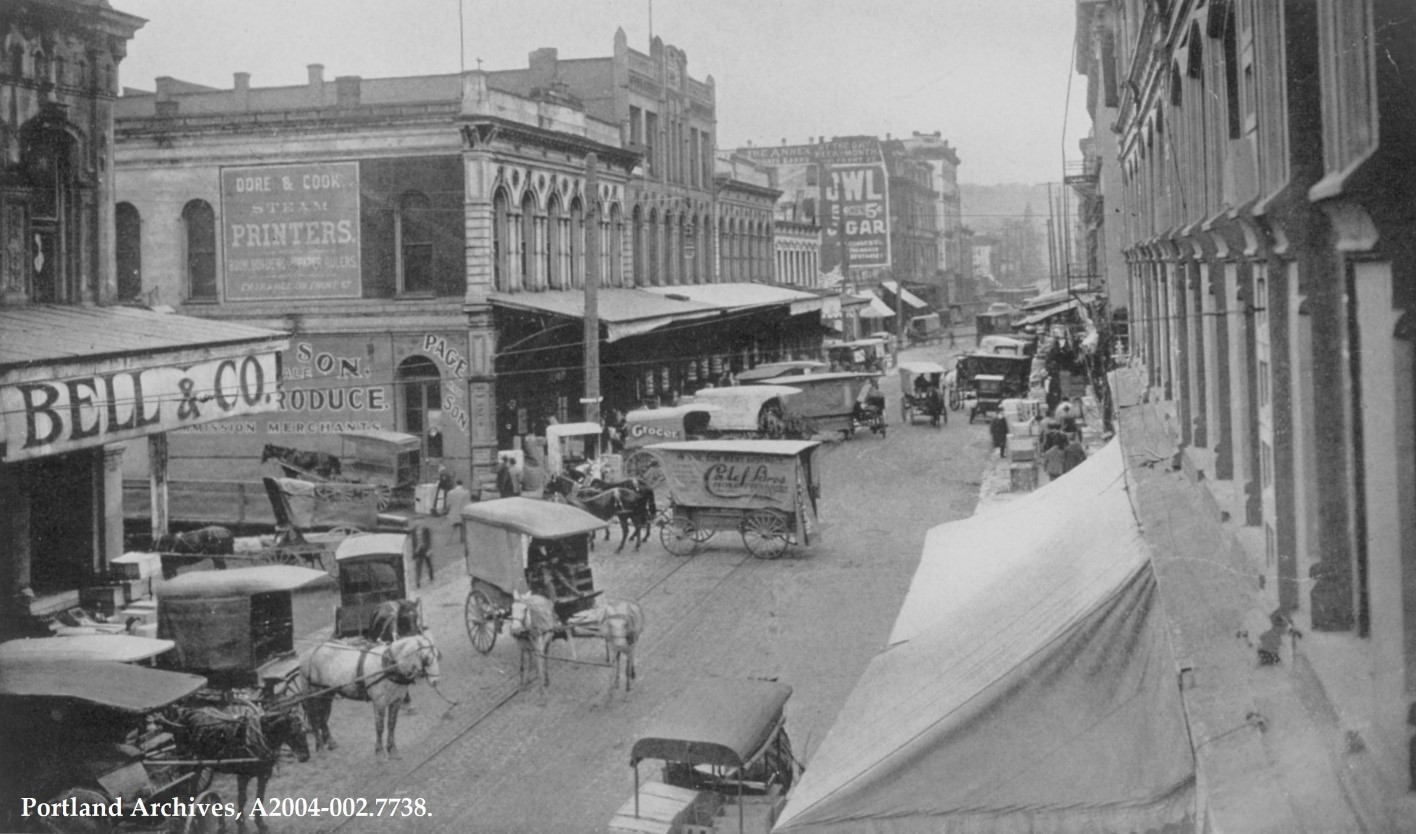

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2004-002.7738. ca 1910. As this image of Front Street around 1910 shows, horses were integral to Portland's shipping and economy. The elevated platforms along both sides of the street allowed wagons to back in and men to load goods without climbing up and into the wagon each time.

In the image above, the horse-drawn shipping of Front Street was critical to the economic vitality of Portland and the overall well-being of the populace. Note that the horses have backed in to the sidewalk. In turn-of-the-century cities, businesses often relied on ramp systems to transport goods from cart to cellar. Building cellars were often the obvious place to store goods, but carrying each load into the building and down the stairs was cumbersome. Instead, ramps from the adjacent sidewalk ran down to the basements, which closed with flat doors so pedestrians could walk over them during non-delivery hours. Merchants followed suit by bringing long planks that extended from the carriage down to the ramps.

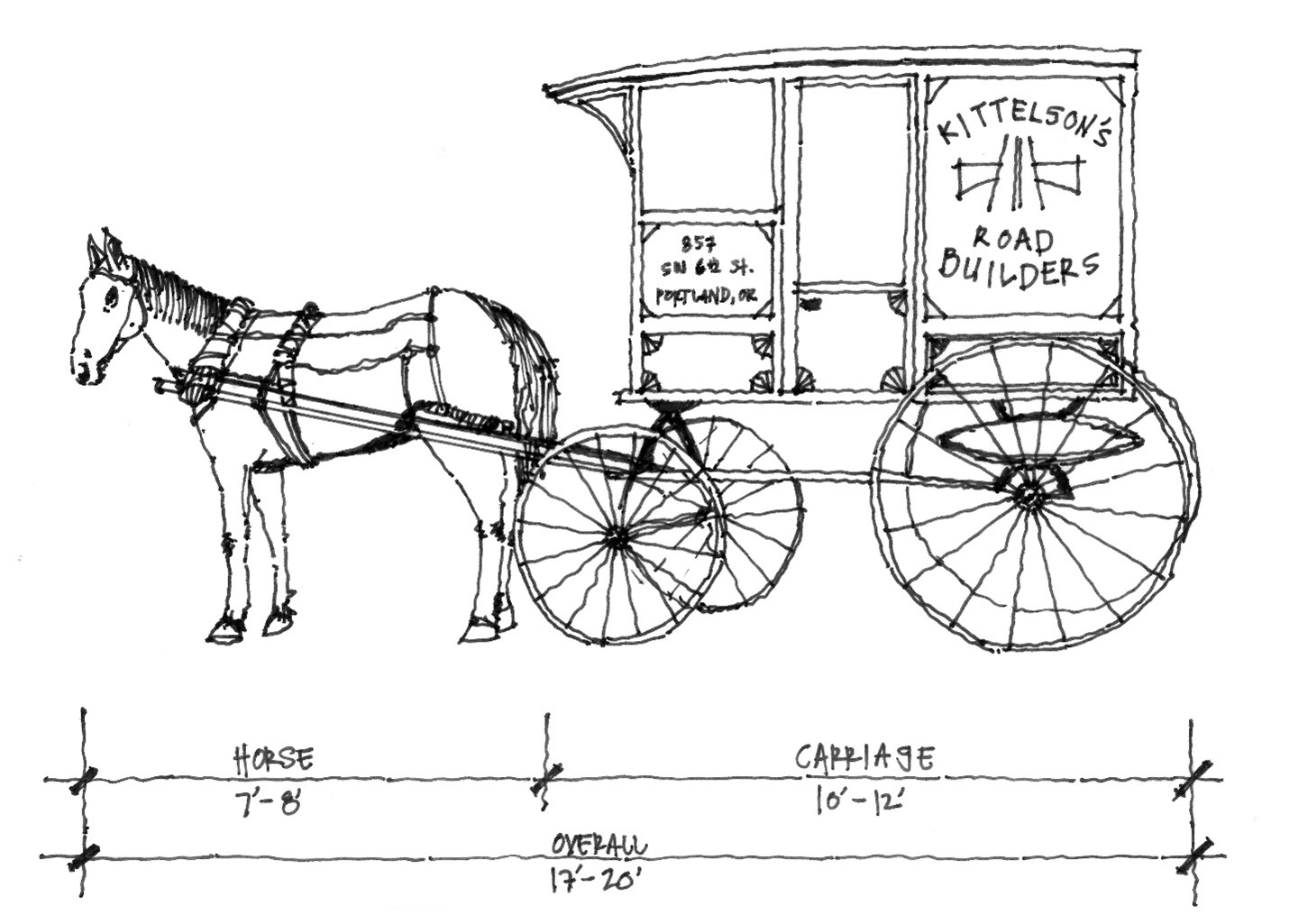

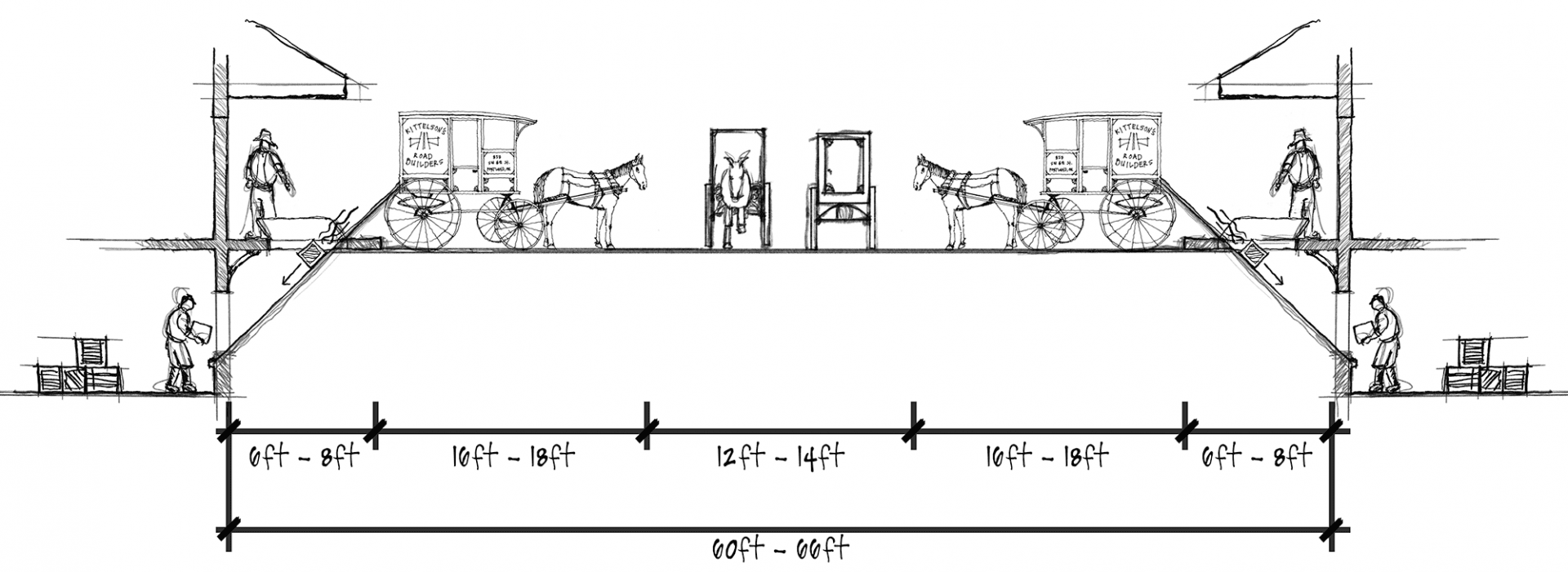

Drawn by JP Weesner.

The average horse is about eight feet long, and its accompanying cart or carriage varied between eight and ten feet in length. Carriage bottoms are around four feet. The slope down to the basement of a typical building might require approximately four to six feet of drop. Overall, the drop might need to be eight to ten feet. Using a 1-1 ratio (45-degree angle) to slide products from the cart to the basement means the width of a given sidewalk area from the face of the building to the curb would range between six and eight feet, and the backed-in horse would need around 16 to 18 feet to be “parked” and out of the way of moving traffic. If we mirror this dimension across the street (which would have been around 12- to 14-feet wide for two horses to pass by) we get around 60 to 66 feet. The average downtown street right-of-way in Portland today? 60 feet.

Drawn by JP Weesner.

As Portland and other similar cities have organically grown and accommodated new modes of transportation, the widths and uses of the public right-of-way have shifted. Travel lanes are wider, back-in parking has been replaced with parallel parking, sidewalks have remained somewhat the same. Now, street trees grow where hitching posts once stood-but make no mistake, horses have given us the fundamental dimension of size and scale of our pre-automotive streetscapes.

The horse-powered system was not perfect, however. One of its greatest flaws was overreliance. So many cities depended nearly exclusively on horses to function that an 1872 outbreak of equine influenza hobbled cities for weeks across the United States and Canada. When the virus hit a city, its horse population became too ill to work in a matter of days. Without equine motors to carry people from point A to point B, public transit service halted, real estate sales stopped, and markets fell. As we look toward an electric, automated, and sustainable future, we should look at the horse-powered city as a cautionary tale and be mindful that overreliance on any one form of energy can spell disaster in a time of crisis. This will be especially crucial given the forecasted impact of climate change on extreme weather and natural disasters.

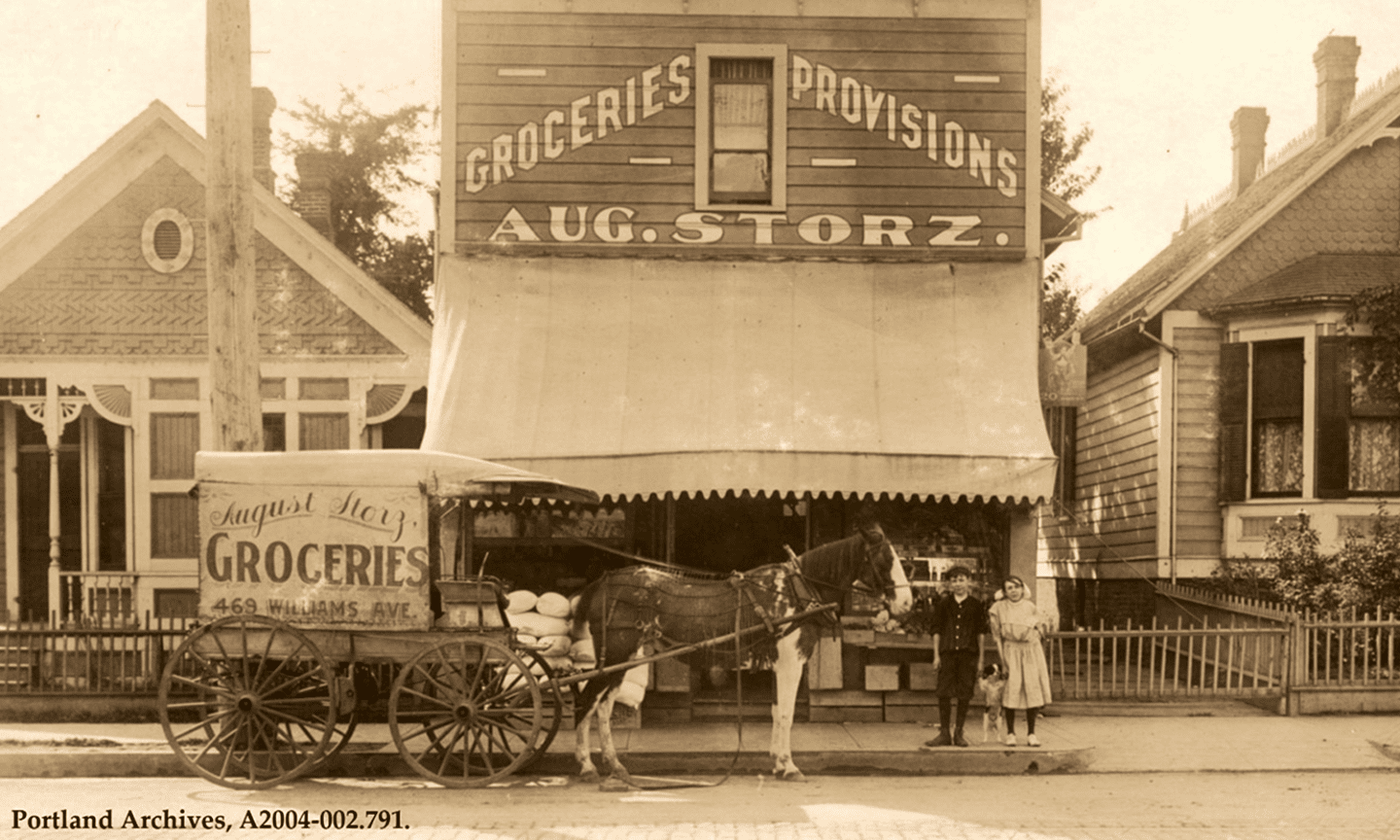

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2004-002.791. 1910. Horses provided the motive power behind Portland's small-business economy well into the twentieth century. Fine-looking horses, like the one posed here outside August Storz Grocery at 221 N Williams, even helped advertise a store's quality and respectability.

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2004-002.693. 1894. Urban horses were subject to many types of working condition, including flooded streets like the one depicted here in north Portland.

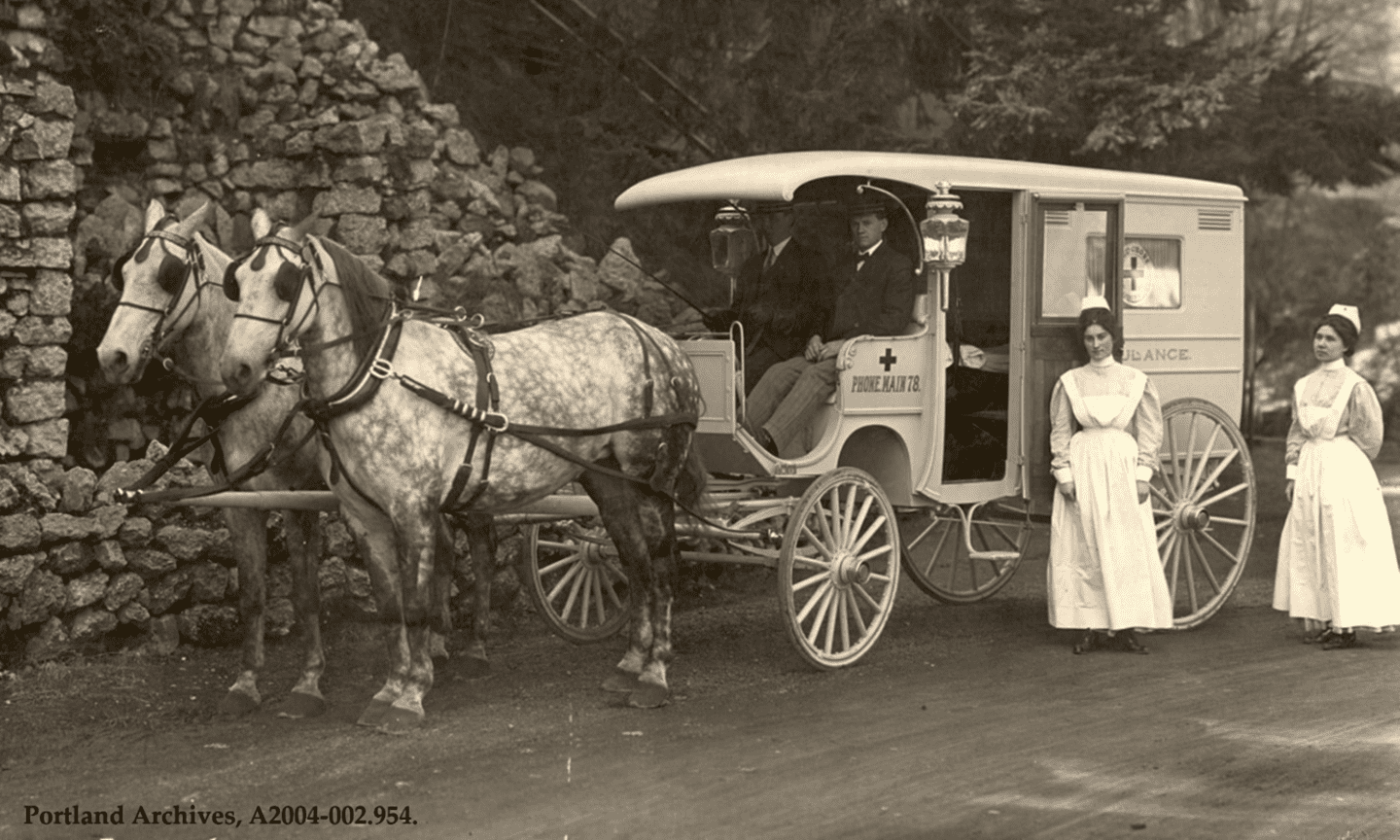

City of Portland (OR) Archives, A2004-002.954. ca. 1910. Horses played a vital role in Portland's urban healthcare system too. Here two large dappled grays pull an ambulance and its crew.

City of Portland (OR) Archives, AP/73981. 1910. Fire horses were highly-trained and specialized urban workers. Not only did fire horses have to run toward a burning structure while pulling a heavy engine, they had to wait calmly while men worked to put out the fire. Many fire horses were trained to assemble in formation to the station bell, and their harness would be lowered from rigging above. In this photograph, Portland's Truck 1 horses race past the Museum of Art. Clearly, fire horses were granted an exception to city speed limits.

About the Authors

Jennifer Marks is a publications coordinator and technical editor at Kittelson. The topic of horses and transportation is of particular interest to Jennifer, who is completing a Ph.D. dissertation entitled “Creature’s Metropolis: How Animals and Humans Built Chicago, 1870-1930,” examining how human and animal relationships transformed urban technology and the built environment in turn-of-the-century Chicago. Jennifer has 15+ years experience working with horses and has a 24-year-old horse named Ace.

JP Weesner is a practicing landscape architect and urban designer. He provides urban design solutions that integrate built environments with implementable projects and leverage transportation infrastructure with “placemaking” to create walkable, livable, and context-relevant places. JP is a self-titled “urban forensic archaeologist” and loves to dig into the culture, history, and social fabrics of places to better understand urban form and structure. JP has spent 20+ years working on downtown master plans, transit-oriented and infill developments, multimodal streetscapes, traffic calming and “road diets,” and implementing Complete Streets.

References

Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America (Ann Norton Greene)

The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century (Clay McShane and Joel A. Tarr)

Gelded Age Boston (Clay McShane)