August 13, 2025

When we think of transportation and health, our minds often jump straight to traffic safety or walkability. But transportation system design has the power to shape the physical, social, and mental well-being of entire communities. Did you know that lighting and noise generated by transportation infrastructure affect people’s health and mobility? How about that orienting cities around active transportation can improve resident’s and visitor’s mental health, social connection, and even their lifespans? It’s true. Thoughtful transportation design drives real health outcomes.

Health is often conceptualized as the absence of disease, but in reality, health describes a complete state of physical, mental, and social well-being. Much of the work we do as transportation professionals connects to the social determinants of health, which are the nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes. Expanding our definition of healthcare from disease management to one that encompasses the design of healthier, more livable cities can help us align our efforts to improve health outcomes and prevent disease.

This article reframes four factors that transportation professionals can consider to improve the health and well-being of communities they support: lighting, noise, accessibility for older adults, and urban design.

The Psychology of Lighting

Because how we navigate spaces is highly influenced by what visual information we receive, lighting is a major factor in how we move through our community. Light gives physiological cues but also psychological ones. Lighting levels can induce or abate psychological responses like fear, an emotion that impacts how and whether we take advantage of active transportation.

Fear can be broken down into objective and subjective fear. Objective fear relates to quantifiable statistics of crime, such as the rate of violent crime, whereas subjective fear is an individual’s perception of fear and safety, such as feeling safe walking home at night. Subjective fear is the greater predictor of whether someone will choose to use active transportation, as it influences how people interact with public spaces.

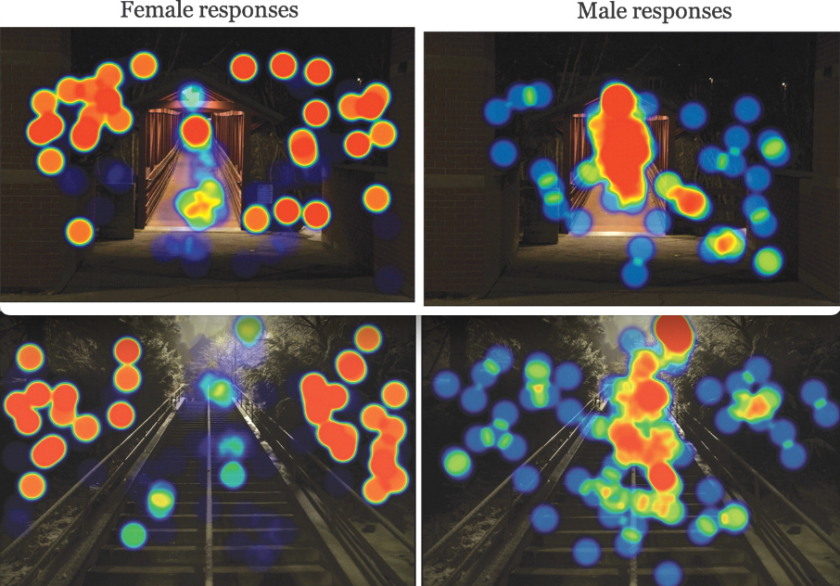

Age and gender contribute to differences in how people experience moving through public space. For example, research indicates that when walking, women tend to experience a higher level of subjective fear. They typically scan their environment more, whereas men tend to look straight ahead. Improved lighting along the periphery of walkways allows women to observe spaces of concern with higher visibility, helping decrease fear and encourage use of pedestrian facilities. Other research indicates that increased lighting uniformity, higher illuminance levels (measured in lux), and brighter lighting can enhance perceived safety in public spaces.

Men and Women View Public Spaces Differently

Source: Chaney, Robert A., Alyssa Baer, and L. Ida Tovar (2024). Gender-Based Heat Map Images of Campus Walking Settings: A Reflection of Lived Experience. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2023.0027.

Proper lighting is important, and getting its placement and intensity right is just as essential. There is such a thing as too much light. An overabundance of artificial light has been shown to negatively impact health. And some research indicates that a lux over 10 begins diminishing returns on lighting. Nondirected lighting can affect sleep quality by suppressing melatonin production and increase the risk of developing mental health disorders.

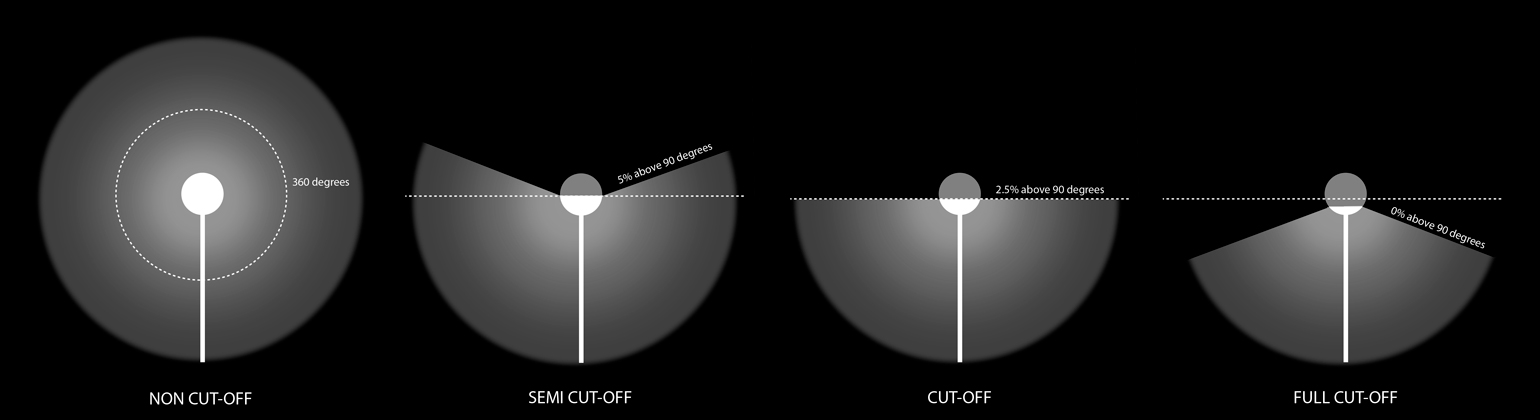

To prevent these negative impacts, light shielding techniques can be used to direct lighting toward the street and away from homes. Balancing strategic light levels, placement, and direction can improve a sense of safety while reducing negative externalities.

Light Shielding Techniques

Source: Schlickman, E. (2018). Illuminated Futures. https://urbanomnibus.net/2018/06/illuminated-futures/

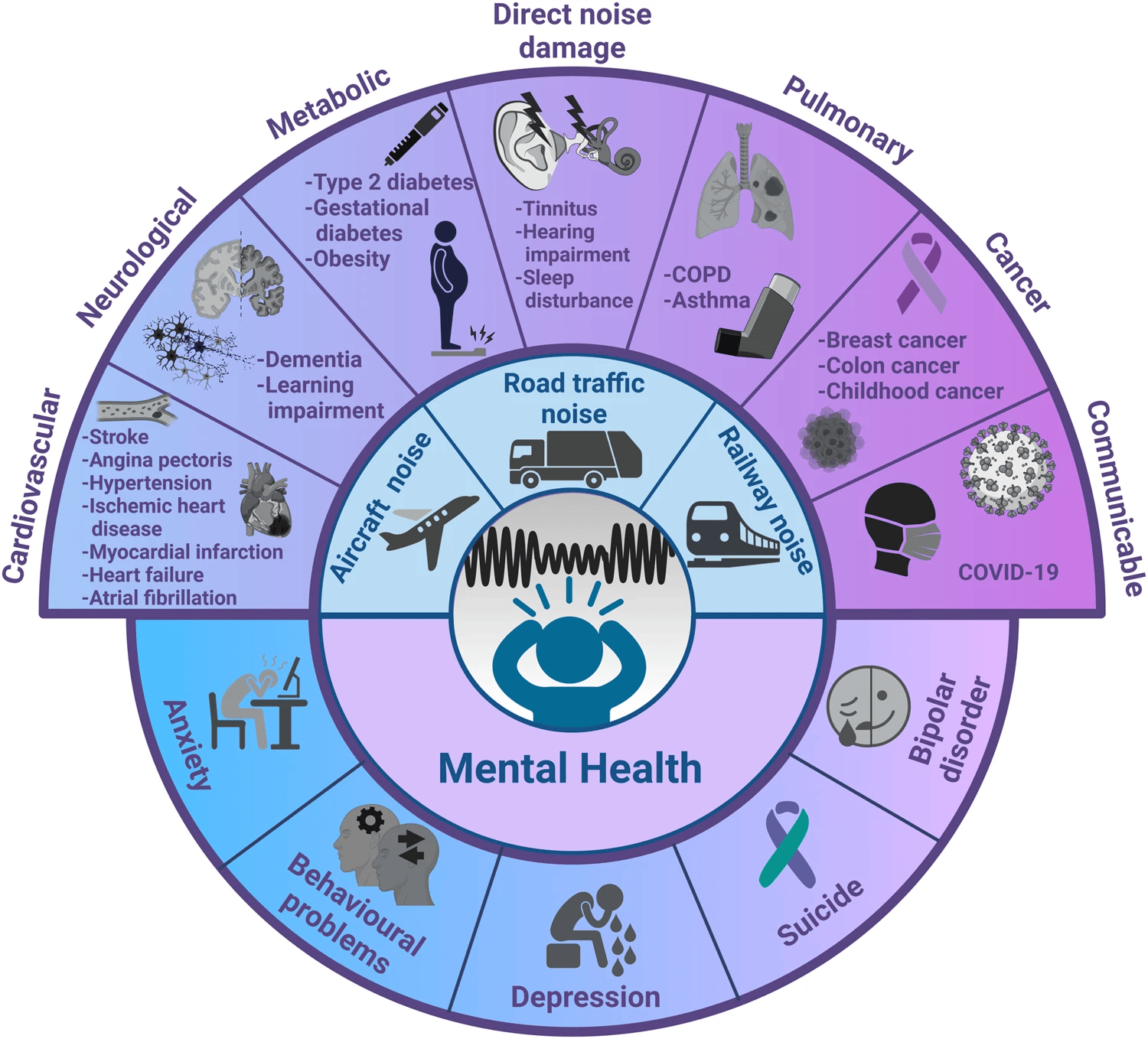

The Adverse Health Effects of Noise

Chronic environmental noise, especially from traffic, can negatively impact mental health. Evidence reveals strong links to sleep disruption, depression, anxiety, and even structural changes in the brain. Chronic noise from a typical decibel range of 50–70 decibels can lead to long-term, heightened stress responses, which can increase endocrine activation and sympathetic nervous system impacts. This, in turn, can lead to increased cardiovascular risks, elevated risk of chronic disease, and heightened levels of inflammatory cytokines in the blood. Like air pollution, noise exposure isn’t distributed equally. Communities of color and low-income communities often experience higher levels of traffic-related noise, and the health effects compound over time.

Designing infrastructure with these effects in mind can help diminish the adverse effects of our transportation system. High speeds are a common cause of traffic noise, so reducing speeds using traffic calming measures, such as raised crosswalks, roundabouts, chicanes, and curb extensions, can lead to healthier surroundings.

Another approach is to reduce the noise that infiltrates spaces by building sound walls, which are walls near high-traffic spaces, and planting trees to redirect or absorb road noise. Other interventions include designing walkable communities to take traffic off the road; creating quiet parks, which are acoustically protected areas; and integrating gray noise into spaces. Gray noise adds ambient sound to the area by making changes like installing fountains and planting foliage for bird habitat.

Noise Affects Body Systems and Mental Health

Source: Hahad, O., Kuntic, M., Al-Kindi, S. et al. Noise and mental health: evidence, mechanisms, and consequences. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 35, 16–23 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-024-00642-5

How to Support Aging in Place

Aging in place is the ability for someone to stay within their community and home for as long as possible. Uprooting to relocate to a senior living facility can be disorienting and even isolating. When older adults can live within their community, they can draw on their routines, social connections, and placemaking to support their well-being as they age.

During the aging process, people typically lose their ability to drive and instead must rely on rideshare, walking, and transit to get around. Less walkable or transit-accessible communities can isolate older adults and make it arduous to access resources like healthcare, especially for those with mobility challenges. Moreover, having access to active transportation can make a critical difference in physical health. Older adults who walked an hour a day were able to live in their homes for an average of 6.7 years longer than people who walked 30 minutes or less a day.

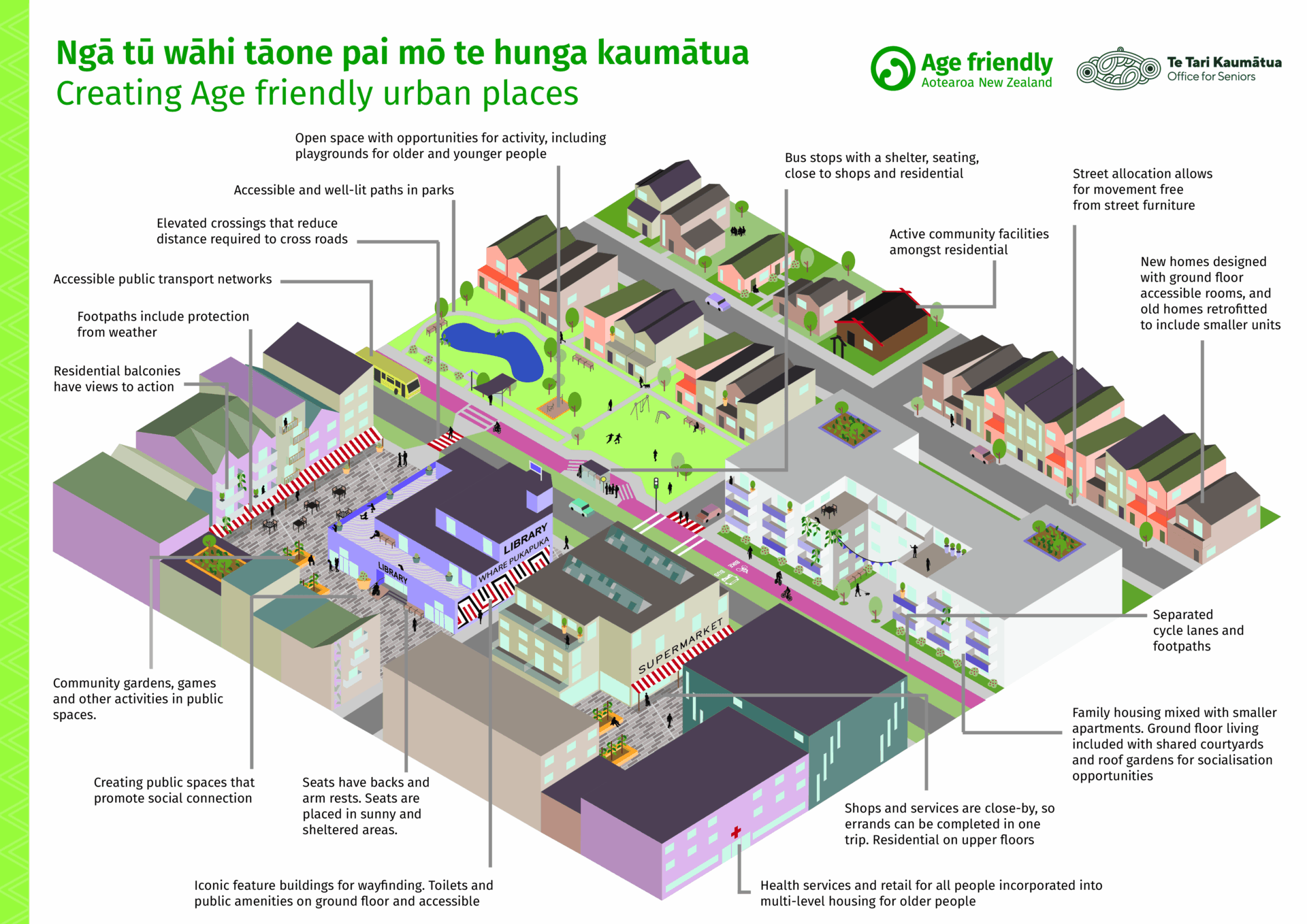

Transportation planning can support aging in place by designing infrastructure that accommodates varying levels of mobility and promotes accessible active transportation. Design features that support aging in place can include changes to the built environment, like ADA-compliant walking areas, shade features, covered bus stops, benches for resting, and median refuge islands. Changes in service—like extended crossing times, residential transit services, audible walk signals, automatic pedestrian recall, and lower traffic speeds—also make a big difference.

Elements of an Age Friendly Urban Place

Source: Age Friendly New Zealand,. (2018). Age Friendly Urban Places. https://www.officeforseniors.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Age-friendly-_Urban-Places_interactive.pdf

Ways to Build More Active Cities

For people of all ages, the design of roads, sidewalks, transit stops, and public spaces has far more of an effect on our mental and social well-being than we might realize. Wide roads with no safe crossings, long distances between bus stops, and poorly lit or unwelcoming sidewalks can discourage people from leaving their homes, leaving them feeling isolated and alone. Long commute times are associated with decreased happiness. Over time, for all ages, the cumulative effects of these design decisions reduce physical activity rates, worsen mental health, and reduce social interaction—one of the strongest predictors of mental well-being.

Before the mass adoption of cars in the early 20th century, many U.S. towns and urban neighborhoods were built for walking. They had dense, mixed-use development; active main streets; and many public gathering spaces. These pedestrian-oriented environments were gradually deprioritized once mass-produced automobiles came about in the early 20th century. Car-centric planning was intensified in the 1950s by suburban sprawl, strip malls, and highways. These changes dramatically reshaped the American landscape and how people got around.

Designing infrastructure with active transportation in mind can offset these trends and create a more accessible, mobile future for our cities and towns. Wide shared-use paths, enhanced public transit, pedestrian spaces, and traffic calming features like pocket parks or street patios can all bolster connectivity, social interaction, and a sense of community. Shorter block lengths can reduce crossing distances, which can help reduce pedestrian crash risk. In other words, designing for all road users—pedestrians, drivers, bicyclists, and anyone else who needs to use a street—is one of the best ways to encourage movement and improve community health and well-being.

Continuing the Conversation

Transportation design shapes more than just how we move; it impacts how we feel, connect, and age. By creating accessible, connected, and inviting public spaces, transportation planners can directly support healthier, longer, and more connected lives. With awareness of these health impacts, we can build an interconnected future that uplifts active transportation and everyone who uses it.

At Kittelson, we understand that the work we do has immediate and long-term health impacts. By taking a multifaceted approach, we ensure that mobility is at the forefront of our deliverables. Recently, we created a public health lens for traffic calming to help an agency bridge the gap between professional silos in planning. We also regularly conduct lighting and noise analyses to keep health impacts central to our decision-making.

Reach out to Marcus to learn more about these strategies or the intersections of public health and transportation.