February 11, 2026

In the transportation industry, there’s a misconception that emergency service providers and transportation safety planners and engineers want different things: Firefighters want to go quickly along wide roads with a clear through path, no speed humps, and large turn radii; transportation professionals want folks to go slow down narrow streets with ample traffic-calming measures like curb extensions, speed humps, and median islands. The only thing both groups can seem to agree on is that they want to know why the other side is making their job more difficult.

There is a kernel of truth here. Transportation industry priorities have shifted over time. Rather than exclusively expanding and adding capacity, engineers and planners are now also working to make things smaller and tighter, largely to manage speed, which has a significant impact on the survivability of a crash, particularly when bicyclists and pedestrians are involved.

But in the big picture, firefighters, engineers, and planners are on the same team. We all want to help people get home safely and to save lives. To better understand both sides of the equation—and correct this misconception that undermines our shared goals—we sat down with firefighter emergency medical technician (EMT) Adam DeVore, who has more than a decade of experience fighting fires and responding to emergencies in Portland, Oregon; Dave Zuckermann, former Bay Area park ranger and wildland firefighter; and a coterie of Kittelson engineers and planners, all of whom have experience partnering with emergency services on projects.

Adam DeVore is a firefighter EMT in Portland, OR, where he’s worked for 18 years. He also spent a collective six years working on wildland fires with the U.S. Forest Service in Nevada and the National Parks Service at Sequioa and Kings Canyon national parks in California. Photo credit: Adam DeVore.

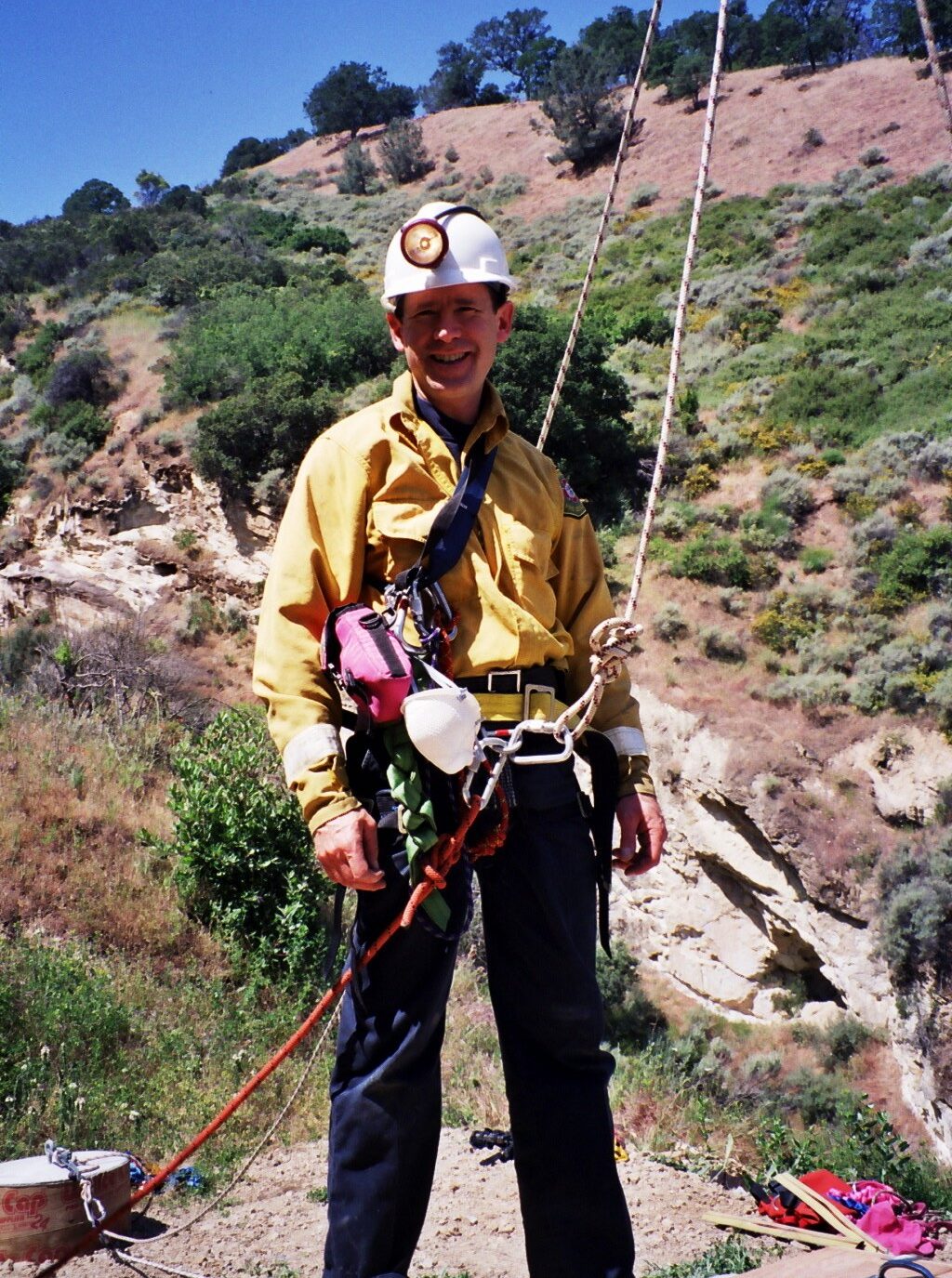

Dave Zuckermann joined the East Bay Regional Park District fire department in the mid 1990s, shortly after Oakland’s Tunnel Fire. He retired from fire in 2006 but continued working in the parks until 2020. Photo courtesy of Dave Zuckermann.

What You Should Know About Firefighting

In 2023 (the most recent year of data available), there were more than 340,000 residential fires and 110,000 nonresidential building fires in the U.S. Collectively, these events killed more than 3,000 people and injured another 11,000. That same year, there were just over one million career and volunteer firefighters working in the U.S.

In cities across the country, firefighters do a lot more than fight fires. They respond to medical emergencies, drug overdoses, car crashes, gas leaks, and downed power lines. (In fact, most calls answered by firefighters are medical emergencies rather than fires.) And they do so with an impressive array of specialized, heavy-duty vehicles, including:

- fire engines (or pumper trucks), which carry water and hose for fire suppression. They are generally 30–35 feet long and can weigh upwards of 40,000 pounds and carry more than 1,000 gallons of water. Wildland fire engines are smaller and often have four-wheel drive to help firefighters access remote areas over rough terrain;

- fire trucks (including ladder trucks, tower ladder trucks, and rescue trucks), which have tools and/or extendable ladders for rescues. Ladder trucks are typically 40–45 feet long and weigh up to 70,000 pounds. Ladder trucks need to be big and heavy to balance the horizontal and vertical reach of their 100-foot-long aerial ladder. Some trucks, called tillers, have articulated front and back sections that can be independently steered; and

- quints, which are combination trucks equipped with both an engine’s water-pumping infrastructure and a truck’s toolkit capabilities.

Engines like the one that DeVore drives in Portland, OR, carry thousands of gallons of water and can weigh up to 40,000 pounds. Photo credit: Adam DeVore.

This Los Angeles Fire Department tiller helps illustrate just how long some firefighting vehicles can get. Despite its length, this truck is surprisingly nimble thanks to the second steering cab in the rear. Photo credit: Matthew Field, Wikimedia Commons.

When responding to an emergency, even small delays can have a significant impact on outcomes. “Time is of the essence. Every 30 seconds a fire doubles,” says DeVore. “If you have to spend five minutes turning around, that’s a big difference.” And in the case of sudden cardiac arrest, survival rates can be as high as 90% if treatment starts within the first few minutes. For each minute longer, survivability drops by 10%. Rapid access to medical care also plays a crucial role in the survivability of car crashes. So much so that post-crash care is one of the five pillars of the Federal Highway Administration’s Safe System Approach.

But urban infrastructure can make responding to any of these emergencies a real challenge. The particularities of a given street—and the type of truck or engine being driven—changes how firefighters respond. “There are roads we can’t go down,” DeVore explains. “Which means we can’t get to your house because we can’t fit, and we have to take extra time to park around the block and pull hose down the road or carry our EMS gear to you.” Fire engine drivers like DeVore must navigate their rigs through narrow neighborhood streets, where cars frequently park up to already tight corners. Concrete medians, even with cutouts, can make turning off main response routes impossible. These challenges are compounded by passenger vehicle drivers who don’t respond predictably to lights and sirens, whether by stopping in the roadway or pulling left instead of right.

DeVore estimates that his southeast Portland station responds to 8–12 calls a day, about 80% of which are medical in nature. The remaining 20% of calls are car crashes, fires, or other emergencies. Each of these events requires specific tools: automated external defibrillators for restarting heart rhythms, hydraulic rescue tools for extracting injured passengers, plus radios, thermal cameras, maps, plans, hose, nozzles, and a lot more for fighting a fire. “I like that we are the problem-solvers, but that means our rigs aren’t getting any smaller,” says DeVore. “We’re always being asked to do more, so we’re always carrying more stuff.”

Each side of an engine is full of compartments that hold specialty tools and equipment for medical crises, fires, and other emergencies. Photo credit: Adam DeVore

And fires require not just one engine or truck but multiple of both. DeVore describes firefighting like a symphony. Different rig teams play highly specialized roles, all of them working together to suppress the flames. Take a moderately sized house fire. Once the call comes in, four engines, two trucks, and two pickup trucks must pass through city and neighborhood streets as quickly as possible to reach the scene—that’s eight simultaneous trips generated for a single fire. The first engine to arrive hooks up to a hydrant if one is nearby and searches for location of the fire (called the “seat”) as quickly as possible. The second engine will lay hose through the street to get water back to that first engine. The third engine serves as the backup line, protecting the way out for firefighters inside, while the fourth engine parks nearby and is on deck to rescue firefighters should anything go awry. The two firetrucks look for the seat, facilitate engines’ access to the fire, and conduct any search and rescue activities. Firetruck crews are also responsible for ventilation. Two chiefs—one acting as an incident commander and one acting as a safety officer—are the conductors of this symphony. Between the engines, the trucks, and the pickups, there could be upwards of 265 feet of vehicle vying for space around a single home. The survivability of this event, for both life and property, depends on each of these vehicles getting into position as quickly as possible.

Fires in high rises are even more complicated and require specialized stairwell protection teams and radio communication strategies. High-angle rescues, trench rescues, and hazmat situations require similarly nuanced responses, each with their own large vehicle with specialized equipment for that situation.

At house fires, curb space is in high demand. Here, a fire truck and a fire engine or other specialized vehicle park alongside a housefire in Marietta, Ohio. Photo Credit: Courtney Wentz on Unsplash.

Other Things You Might Not Know—but Should—About Firefighting

- Truck and engine drivers choose their routes. They know the local road network intimately and are constantly doing the mental calculus of which intersections have extra lanes at stoplights for going around traffic and which ones are difficult to pass through. They also have access to a mobile data terminal with a map of all the nearby hydrants, speed bumps, and other important infrastructure to help inform their route.

- Driving a truck or engine is (as expected) very fun. According to DeVore, the best seat in the house is the rear of the tiller truck: “In the summer, we drive around with both the doors open and everyone waves.” DeVore says driving is also hard: “Rigs are really difficult to maneuver. We need space to do it.”

- Speed humps are less of a problem for causing a rough ride and more for how they slow down the truck or engine. Seconds and minutes count, and when an engine or truck needs to blitz sirens-on down a roadway, it means they need to blitz sirens-on down that roadway. Sirens on means a team is trying to get tools, water, or a defibrillator to someone whose life is on the line.

Fire engine and truck drivers select routes using their own mental maps and information on hydrants and speed bumps from a mobile data terminal. Photo credit: Adam DeVore.

The Added Challenge of the Wildland-Urban Interface

Each year in the U.S., more than 73,000 wildfires burn an average of 7 million acres of private, state, and federal land. Tackling these fires is no small feat, as—in addition to the actual fire—teams must brave low to no visibility, steep and uneven terrain, and mixed land uses.

Steep, uneven terrain makes wildland firefighting especially difficult. Photo credit: U.S. Forest Service.

Wildland firefighters work to protect people, property, and the environment—in that order. This hierarchy gets especially muddled in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), where human development butts up against or mixes with natural landscapes. The WUI is especially hazardous for two key reasons: it creates greater opportunity for human-sparked fires in undeveloped areas, and it increases the number of people and structures in harm’s way should a fire break out. In the U.S., more than 60,000 communities are at risk for WUI fires, and nationally, the amount of land in the WUI grows by approximately two million acres each year.

In the WUI, firefighters encounter forests, chaparrals (shrublands), and grasslands but also roads, housing developments, and even bridges. Driving a wildland rig through these areas creates new challenges. As smoke fills the air, drivers are effectively blinded. They have to proceed foot by foot or send a spotter to walk ahead. Many bridges lack posted weight ratings, so teams have to inspect them in real time to make sure they are safe to drive over.

Drivers also have to always be thinking about their exit plans. For an urban fire, firefighters can set up in relatively static positions. But at a wildfire, teams have to be ready to leave at a moment’s notice. “We always park facing out, and we never attach a hose to a hydrant unless we’re just filling up,” DeVore said. “You don’t stay attached in case you have to cut and run.” Exit plans get even more complicated when there is only one route in and out of a community. In a wildfire emergency, that one road has to serve as both evacuation route and emergency service access.

In the WUI, human-made development—in this case utility poles, barbed wire fence, roadway, shrubs, and trees—mingles with the natural landscape and increases fire risk. Photo credit: U.S. Forest Service.

Typically, wildland fire suppression relies on teams for structural protection and teams for fire attack (fighting the fire itself). Other teams go to houses and help make sure people are evacuating.

The approach to wildfire suppression in the U.S. has changed over time. For a long time, all fire was suppressed. But increasingly, scientists and firefighting organizations recognize the important role small, controlled fires play in maintaining healthy ecosystems and preventing larger, more destructive fires. Lessons learned from larger disasters have informed both firefighting processes and city policies.

Retired park ranger and wildland firefighter Dave Zuckermann remembers hearing stories from his colleagues who worked the 1991 Tunnel Fire, which burned more than 1,500 acres across Oakland and Berkeley, California. That October, Diablo winds—hot dry winds from the northeast that occur in the Bay Area in the spring and fall—reignited hot spots from a brush fire that had burned the day before. Narrow, steep, and winding roads, debris, and low visibility made evacuations especially treacherous. Roads became choked with congestion from evacuating residents, sightseers, and emergency personnel. Water supply was also an issue, particularly when engines from outside Oakland couldn’t hook up to Oakland fire hydrants due to a half-inch difference in hose coupling sizes.

After the fire, California updated its fire code to mandate defensible space around buildings, and the City standardized hydrant connectors and improved radio communications. According to Zuckermann, fire management in general is now far more proactive instead of reactive. Parks—popular areas in the WUI—manage woodlands by reducing fuel, often replacing exotic plantings with native species and bringing in goats and sheep to naturally manage grass and brush. They even use fire: to manage eucalyptus woodlands in California, parks staff rake slash (fallen bark, limbs, and leaves) into piles and burn them over the winter.

Vegetation management is now a crucial aspect part of fire management in the U.S. Here, U.S. Forest Service staff trim dense brush to reduce fire risk in the San Bernardino National Forest. Photo credit: U.S. Forest Service. (USDA Forest Service photo by Andrew Avitt)

Other Things You Might Not Know—but Should—About Wildfires

- Big fires can make their own weather. Heat from the fire creates wind, which then can blow embers in unpredictable directions. Really large fires can create enough clouds to cause thunderstorms and currents that form into fire tornados.

- Some plant species rely on fire to reproduce or grow. The lodgepole pine, for example, needs the heat from wildfires to melt the resin that encases their cones and release the seeds. Fires also release essential nutrients back into the soil that plants use as fertilizer to regenerate.

- Nearly 85% of wildfires are caused by humans. Unattended campfires, debris burns, equipment, carelessly discarded cigarettes, and arson are some of the most common culprits.

What Transportation Planners & Engineers Can Do

Now that you have a better understanding of the demands and nuances of firefighting in cities and in the WUI, you’re probably wondering how you can help. What can you do as a planner or engineer to support both better emergency response in your projects and make firefighters like DeVore’s jobs a little easier? Lots! You can:

- Start with context. To get designs that work in real life, we first need to understand a community’s context—the land use patterns that determine appropriate road characteristics, speed, and safety treatments. In addition to how people use community roads (whether they walk, bike, take transit, or drive), we need to consider how emergency vehicles and first responders navigate the local network. Remember that because drivers like DeVore choose their routes, the fire department will know which routes and movements they regularly use during emergencies; use this information to shape your design decisions. Also check your standards to see whether they have been tailored to your community’s unique context. Standards borrowed wholesale from other agencies and standards that haven’t been updated in decades can both lead to infrastructure that works against, rather than with, community context.

- Meaningfully involve emergency services from the beginning. Firefighters and other EMS providers are experts in their fields and know what infrastructure they need to be successful in their duties. Putting representatives from these spheres into collaborative, decision-making positions from the beginning helps make sure your plans and designs for a community will meet both the project goals and their unique needs. For example, the City of Austin, Texas, developed designs that were preapproved by local EMS agencies. Including these agencies in the decision-making process expedited the City’s implementation of mutually beneficial improvements.

- Be ready to explain the how and why. For firefighters and other emergency service representatives on your project, this might be their first time through the planning and design process. Create a space of collaboration by explaining how the project will proceed. This way, everyone is on the same page about who reviews, who approves, and when major milestones occur during planning, design, and implementation. Firefighters and emergency services representatives may also be unfamiliar with different roadway treatments. By explaining all available options and the research data behind them, you establish a shared vocabulary and understanding. Visualizations that show vehicle movements or illustrate how a design would function can help communicate complex ideas.

- Listen, ask questions, and incorporate feedback. Take time in planning and design meetings to understand emergency services’ goals and concerns. Demonstrate your care and openness by asking questions about local fire response procedures, the order of operations in responding to an incident, and what types of trucks and engines need to navigate the streets in your community. From these conversations, you might just find that objections to a planned curb are really just a need for vehicles to have enough space to put out their stabilizers, and that reducing the height of that curb makes the lane functional for both firetrucks and bicyclists.

Stabilizer arms help level and secure the rig when the aerial ladder is being used. Photo credit: Nick Wilbur, Fire Engineering, https://www.fireengineering.com/fire-apparatus/aerial-apparatus/stabilizers-the-foundation-of-the-truck/.

- Get your design vehicle right. Different emergency vehicles have different size and turn radius needs, and each station has access to specific rigs. Do your homework to find out what rigs operate on your streets. Also take a note from the Tunnel Fire and consider whether an extreme enough emergency could warrant rigs coming in from neighboring communities. Can those larger rigs still navigate the street or intersection? As you answer that question, don’t simply run a model in some software. Take time to find out what the experience might be for the driver who has to steer thousands of pounds of vehicle around that turn, sirens on, en route to a life-and-death situation.

- Go outside, together. Take project partners to check out real-world conditions. Hitting the streets creates opportunities to answer questions and address concerns before pen hits paper. If there are concerns with how particular vehicles will navigate a design on paper, put down some cones and test your footprint or, if you are working on a roundabout, host a roundabout rodeo.

- Get creative. Could that physically separated two-way cycle track be opened for an ambulance in an emergency? Might small passenger cars be able to use that multiuse path for an evacuation? Is there a slope and/or height for those speed humps or speed cushions that works for all parties? Ask what you can tweak about a design to better accommodate fire and emergency vehicles. Remember too that creative solutions often come with dimensional and pavement design needs that are best considered early on.

- Think by spot and by system. Understand how proposed changes will impact emergency response operations, both in the immediate project area and throughout the system. For example, a couple seconds of delay due to a speed cushion in one spot may not be a deal breaker, but a couple seconds at fifteen spots might add up to that thirty seconds a fire needs to double. Consider all phases of your project. Detour routes, lane closures, and congestion during construction can all have an impact on emergency response.

- Think about emergency services Don’t wait for a big disaster to spark evacuation and emergency management planning. Getting fire and EMS representatives involved now will help you plan and design a transportation system that functions under both normal and extreme conditions. Think too about ways to help prepare residents to use the system during an emergency. For example, the City of Ashland, Oregon hosted an evacuation drill so both City staff and the public knew what to do in the event of a wildfire.

- Start small to build trust. Fire and emergency services have a long history of being left out. Starting small with projects that have broad appeal can help build trust for larger, more innovative improvements in the long run. For traffic-calming efforts, consider building with temporary materials first. Quick-builds can be an effective way to check whether an improvement will cause unexpected challenges for emergency responders. To facilitate trust, be transparent and share findings with first responders along the way.

Stronger, Safer, Together

Far from opposing one another, emergency services and transportation planning and engineering are intimately linked. The roads that DeVore uses to bike around his Portland neighborhood are the same roads on which he drives fire engines when responding to emergencies; they’re also the roads that, should he have an emergency of his own, would keep him safe. They’re also the roads we at Kittelson work on every day. Across these scenarios, the demand for road safety never changes, even if the particularities of who or what is needed to do so shifts. Luckily, roads are complex creations that, like wildfires, create their own weather: just as a road can be designed to balance the needs of various modes, it can be designed to balance the needs of different safety responses.

Firefighters, emergency service providers, and transportation planners and engineers have tremendous power to shape our communities. We can help prevent crashes, plan for disasters, and provide life-saving care if either occurs—but only if we work together.